Jerusalem

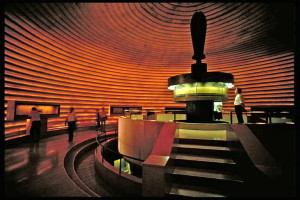

The Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem uses quirky contemporary architecture to house and display ancient manuscripts — including the first Dead Sea Scrolls to be discovered.

The building’s white-tiled dome is shaped like the lid of the first jar in which the scrolls were found at Qumran. In contrast nearby stands a black basalt wall. The black-white imagery symbolises the theme of one of the scrolls — The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness.

The rest of the structure, two-thirds of it below ground level, recalls the caves in which the scrolls were found.

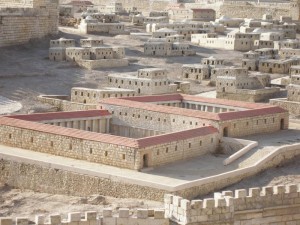

The Shrine of the Book is a wing of the Israel Museum in western Jerusalem. Also on the museum’s campus is an extensive outdoor Second Temple Model of Jerusalem in AD 66, before its destruction by the Romans.

Longest scroll is 8 metres long

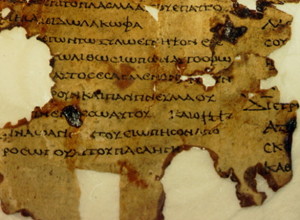

The Shrine of the Book holds all seven of the scrolls found in what is called Cave 1 at Qumran, near the Dead Sea. They are Isaiah A, Isaiah B, the Habakkuk Commentary, the Thanksgiving Scroll, the Community Rule (or the Manual of Discipline), the War of the Sons of Light against the Sons of Darkness (or the War Rule) and the Genesis Apocryphon. All are in ancient Hebrew except the last, which is in Aramaic.

A facsimile of the scroll of Isaiah, arranged around a huge elevated spindle, provides a dramatic centrepiece in the exhibition hall under the dome.

Also at the Shrine of the Book is the Temple Scroll, the best-preserved of the Qumran scrolls. At more than 8 metres long, it is the longest of the Qumran manuscripts.

The Community Rule is the rule book for the group that wrote or copied the library of scrolls — believed to be a group of Essenes, a strict Jewish sect, who lived an austere lifestyle in their remote desert surroundings.

Cloak-and-dagger negotiations

The uncovering of the Essenes’ literary treasure trove has thrown new light on Israel during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, as well as on the origins of rabbinical Judaism and the Jewish society in which Christianity began.

The discovery, by a Bedouin goat- or sheep-herder searching for a missing animal, occurred in 1947. Israel was on the eve of its War of Independence, a factor that lent a cloak-and-dagger character to negotiations for the purchase of the scrolls.

Professor E. L. Sukenik of the Hebrew University clandestinely acquired three of the scrolls from a Christian Arab antiquities dealer in Bethlehem.

The remaining four scrolls from Cave 1 reached the hands of Mar Athanasius Yeshua Samuel, Metropolitan of the Syrian Jacobite Monastery of St Mark in Jerusalem. In 1949 he took them to the United States and on June 1, 1954, he placed an advertisement in the Wall Street Journal offering “The Four Dead Sea Scrolls” for sale.

The advertisement came to the attention of Yigael Yadin, Professor Sukenik’s son, who had just retired as chief of staff of the Israel Defence Forces and had reverted to his original vocation, archaeology. With the aid of intermediaries, the four scrolls were purchased from Mar Samuel for $US250,000.

Part of the purchase price was contributed by Samuel Gottesman, a New York philanthropist. His heirs sponsored the construction of the Shrine of the Book to house the scrolls.

Scrolls need to ‘rest’

As the scrolls are too fragile to be on display permanently, a rotation system is used. After a scroll has been exhibited for 3–6 months, it is removed from display and placed temporarily in a special storeroom, where it “rests” from exposure.

The Shrine of the Book also displays the Aleppo Codex, the earliest known Hebrew manuscript comprising the text of the Jewish Old Testament. It dates from the early 10th century.

Strictly speaking, as the museum acknowledges, only two or four pages are actually displayed at any one time. Behind them is cardboard modelled to look like the rest of the codex (which is in fact stored in a safe place).

Related site:

Administered by: The Israel Museum

Tel.: 972-2-6708811

Open: Sun, Mon, Wed, Thur 10am-5pm; Tues 4-9pm; Fri and holiday eves 10am-2pm; Sat and holidays 10am-5pm

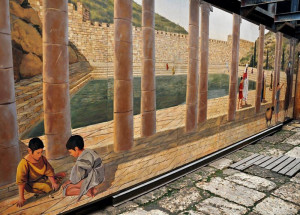

- Inside the main exhibition hall of Shrine of the Book (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Fragment of scroll found in a Qumran cave

- Dome of Shrine of the Book, kept cool by water sprays (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Memorial plaque to D. Samuel and Jeane H. Gottesman, who funded the shrine (Francesco Gasparetti)

- Close-up of spindle displaying facsimile of Isaiah scroll (Seetheholyland.net)

- Black-white contrast symbolising theme of one of the scrolls (© Deror Avi)

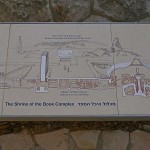

- Shrine of the Book complex (Seetheholyland.net)

- Entrance to Shrine of the Book (Chris Yunker)

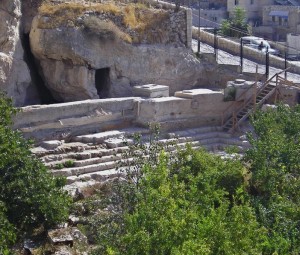

- Cave 4 at Qumran, which held 15,000 fragments of texts (Seetheholyland.net)

- Entrance corridor to Shrine of the Book (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

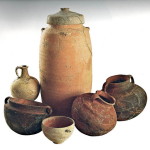

- Qumran display of clay vessels in which scrolls were found (Seetheholyland.net)

- Shrine of the Book in its city setting (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Samaritan sarcophagus from 3rd century, in grounds of Shrine of the Book (Seetheholyland.net)

- Pottery from Qumran (Mariana Salzberg, © Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Vestibule of Shrine of the Book (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

References

Sussman, Ayala, and Peled, Ruth: The Dead Sea Scrolls (Israel Antiquities Authority and Israel Museum Products, 1994)

External links