Israel

The patriarch Abraham pitched his tent and dug a well at Beersheba, a wilderness location identified in the Scriptures as the southern limit of the Promised Land.

About 2000 years before Christ, God had called Abraham, originally from Mesopotamia, to leave his family and possessions and journey to a new land — with the promise that his descendants would become a great nation.

At Beersheba Abraham’s well, on which he depended to water his flocks, was seized by servants of the king of the Philistines, Abimelech.

Abraham complained to Abimelech and struck an oath with the Philistine king, giving him seven ewe lambs for affirming that Abraham had dug the well. To symbolise the covenant affirming his ownership of the well, Abraham planted a tamarisk tree and “called there on the name of the Lord, the everlasting God”. (Genesis 21:25-33)

The name Beersheba (also called Beersheva and Be’er Sheva) means “well of the oath” or “well of the seven [lambs]”. (In Hebrew, the word sheva or sheba means both seven and oath.)

Whenever the writers of Scripture wanted to speak of all Israel from north to south, they would use the expression “from Dan [the northern-most city] to Beersheba” (for example, 1 Samuel 3:20).

Setting for many biblical events

Beersheba, on the northern edge of the barren Negev desert and about 75 kilometres south of Jerusalem, features in several other events of Bible history:

• Abraham and his wife Sarah evicted her slave-girl Hagar and Hagar’s son Ishmael (fathered by Abraham) to wander in the wilderness. But God promised Hagar he would also make Ishmael’s descendants a great nation. (Genesis 21:8-21)

• It was from Beersheba that Abraham journeyed with his son Isaac to Mount Moriah at Jerusalem, where God had ordered him to sacrifice the boy as a burnt offering. (Genesis 22:1-19)

• Isaac, who built an altar to the Lord at Beersheba, also had a dispute with the Philistines over water, and he too resolved it in a covenant with Abimelech. (Genesis 26:18-31)

• Isaac’s son Jacob stole the birthright from his brother Esau while the family camped at Beersheba (Genesis 27:1-40). Fleeing from Esau, Jacob had a dream about angels on a ladder reaching up to heaven (Genesis 28:1017)

• When the elderly Israel (formerly Jacob) was on his way to Egypt, he stopped at Beersheba to offer sacrifice to the God of his father Isaac. God spoke to him “in visions of the night” and encouraged him on his journey. (Genesis 46:1-7)

Ancient settlement contains a well

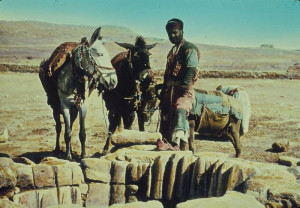

Of the several wells in and around Beersheba, one known as Abraham’s Well is on the southern edge of the old town, where Ha’azmaut Street joins Hebron Road. It is 26 metres deep.

Nearby is the site of a colourful Bedouin market that has operated each Thursday since 1905.

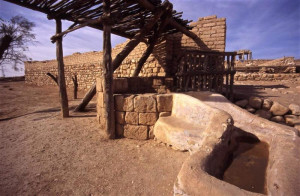

But the ancient settlement from biblical times was located at Tel Beersheba, some 4 kilometres east of the city, on highway 60.

This World Heritage Site also contains a well — dated to the 12th century BC, the time of the patriarchs, and an impressive 69 metres deep — just outside the city gate.

Archaeological excavations have uncovered public buildings, private houses, stables, and a large and impressive water system and reservoir. Extensive reconstruction in mudbrick has been done.

Also on display is a replica of a horned altar, whose hewn stones were found reused on the site. It obviously belonged to an unlawful cult, because it does not comply with the law that an altar should be of “stones on which you have not used an iron tool” (Deuteronomy 27:5).

The altar was probably one of those broken up during the religious reforms of King Josiah (2 Kings 23:8).

The burgeoning modern city of Beersheba is peopled largely by Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union, Ethiopia and other countries. But the past is always present: Redevelopment of the bus station in 2012 uncovered remains of a Byzantine city, including two well-preserved churches.

In Scripture:

Abraham makes a covenant with the Philistines: Genesis 21:25-33

Hagar and Ishmael are sent into the wilderness: Genesis 21:8-21

Isaac makes a covenant with the Philistines: Genesis 26:18-31

Jacob steals Esau’s birthright: Genesis 27:1-40

Israel receives a vision on his way to Egypt: Genesis 46:1-7

King Josiah destroys Beersheba’s high places: 2 Kings 23:8

- Abraham with his family and flocks (József Molnár, Hungarian National Gallery)

- Fresh produce at Beersheba’s Bedouin market (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Entrance to the biblical water system at Tel Beersheba (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Ancient well outside Tel Beersheba’s city gate (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Excavated ancient city at Tel Beersheba (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Tamarisk tree in Israel (Ian W. Scott)

- Reconstructed altar at Tel Beersheba (David Q. Hall)

- Abraham’s Well at Beersheba in mid-1900s, its stones grooved by ropes (© Matson Photo Service)

- Restoration in the ancient city of Tel Beersheba (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Abraham’s Well at Beersheba (Daniel Baránek)

References

Bourbon, Fabio, and Lavagno, Enrico: The Holy Land Archaeological Guide to Israel, Sinai and Jordan (White Star, 2009)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Prag, Kay: Israel & the Palestinian Territories: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 2002)

Stiles, Wayne: “Sights and Insights: Last stop and a point of departure”, Jerusalem Post, May 26, 2011