Bright frescoes and gilded iconostasis in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

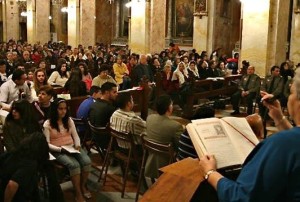

For Western Christians unfamiliar with the rich church decoration and elaborate worship of the Eastern Church, a visit to the Melkite Church of the Annunciation in the Old City of Jerusalem offers a useful introduction.

This unobtrusive building — not to be confused with the towering Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth — is the patriarchate church of Jerusalem’s Greek Catholics.

Usually overlooked by both mapmakers and pilgrims, it is tucked into the patriarchate property in the Christian Quarter. (Entering the Old City through the Jaffa Gate, take the third street on the left — Greek Catholic Patriarchate Road — and the patriarchate is about 50 metres on the right. Descend the stairs to the left of the reception desk and the church door is on your left.)

The separate existence of the Greek Catholic Church dates from 1724, when a split occurred in the ancient Greek Orthodox patriarchate of Antioch and a small group chose communion with Rome rather than Constantinople.

Now numbering 1.6 million worldwide, the Greek Catholics form the second largest Christian church in the Holy Land (after the Greek Orthodox). An Arab church, it has big numbers in the Galilee and a small community in Jerusalem.

Melkite, meaning “royalist”, was originally an uncomplimentary term applied to Eastern Christians who accepted the authority of the 451 Council of Chalcedon and the Byzantine Emperor. The term is no longer used by the Eastern Orthodox.

Frescoes in ‘symphony of colour’

The Church of the Annunciation, built in 1848, is arguably the most representative Byzantine church in Jerusalem.

From the dome down to pew-height, its interior is richly adorned with frescoes in vibrant colours. As writer George Martin puts it, the church “seems alive with prayer even when silent. The vaults and walls . . . are covered in a symphony of colour.”

Christ the Pantokrator in dome of Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

The frescoes, which simulate the stylised motifs of Byzantine icons, were added during renovations in 1974-75. The artists were two brothers from Romania, Michael and Gabriel Moroshan.

In Orthodox tradition, the frescoes follow a clear theological plan. At the top, in the dome, is Christ the Pantokrator, the Ruler of All. Depicted below him, around the dome, are the central act of worship, the Divine Liturgy; the Twelve Apostles; and major prophets and other figures of the Old Testament.

From there, clockwise around the church, the entire life of Christ — from the Annunciation to the Resurrection — is illustrated with profound symbolism. Below is a layer depicting saints, to remind worshippers that these holy people are present during worship.

This description of the scenes from Christ’s life comes from Living Stones Pilgrimage: With the Christians of the Holy Land, co-authored by Alison Hilliard and Betty Jane Bailey:

“Each scene is interconnected: Take the scene of Christ’s birth, painted directly opposite the scene of the Resurrection. Both symbolise why Christ came to earth.

“In the first icon, Christ is born into a stone coffin, a sarcophagus, a symbol of death. His mother is kneeling next to him, dressed entirely in red.

“This is unusual: In the East, the Virgin Mary is normally painted in blue and red — the blue stands for heaven, the red for earth — symbolising the one who combines heaven and earth by giving birth to the God-man. In this scene, however, Mary’s dress is explained by looking across the church at the icon of the Resurrection.

“Here Christ is shown standing on the shattered gates of hell in the form of a cross bridging the mouth of hell. He is resurrecting out of the sarcophagus Adam and Eve, symbolic of mankind. Eve is dressed in red, just as Mary was, showing that the first Eve, who sinned, is replaced by the second one who gave birth to Christ who overcomes sin and raises us to life.

“The second icon therefore completes the scene of the Nativity and explains it theologically. Make the connection from manger to coffin, from swaddling clothes to shroud, from cave to tomb and from birth to death and the new birth of Resurrection.”

Suggestion of final glory

Below icons of saints, curtains are drawn over today’s holy people, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

Powerful symbolism continues around the church. Below the icons of saints, down at pew level, the artists have painted drawn curtains. The suggestion is that, on the last day, the curtains will be pulled back and worshippers will see their own faces glorified.

Across the front of the church, the iconostasis separates the nave from the sanctuary. This screen is richly embellished with gilded icons, Christ depicted on the right of the central doors and the Virgin Mary with the Christ child depicted on the left.

The central doors, known as the Royal Doors, open out to the congregation three times during the liturgy: When Christ comes in the form of the Gospel and a deacon stands in front of the doors to read the text; when the unconsecrated gifts of bread and wine are taken to the altar; and at Communion time when the priest brings out the Eucharist to distribute it to the congregation.

To quote Hilliard and Bailey: “The opening of the Royal Doors is therefore seen to be symbolic of how God erupts into human history — through his Word and his Sacrament.”

As worshippers leave the church, a fresco of the dormition of the Virgin Mary reminds them that they are going back into the world where, inevitably, they will die. Mary’s death is presented as a model for their own deaths as her soul, in the form of a small baby, is being taken to heaven by Christ.

Byzantine liturgy and Orthodox traditions retained

While the Melkites have adopted some Roman Catholic practices, they have essentially retained the Byzantine liturgy and many other Orthodox traditions. Arabic is the main language of worship.

Like the Orthodox clergy, Melkite priests may marry before their ordination.

Melkites make the Sign of the Cross in the same way as the Orthodox — forehead to chest, then from right to left, with the thumb, index and middle fingers joined in honour of the Trinity. The other two fingers are pressed to the palm, in honour of Christ’s two natures, divine and human, in one Person.

Veneration of icons is a common Byzantine practice, respect being paid not to the painting itself but to the person it represents. Some icons are believed to be the means of obtaining miracles, and people pray in front of them for healing or other assistance.

For a sense of the colourful mosaic of Eastern Christian traditions, a small museum in the hallway near the entrance to the church has exhibits of dress, vestments, liturgical items and photos from all of the Oriental churches present in Jerusalem.

Administered by: Melkite Greek Catholic Church in the Holy Land

Tel.: 972-2-6282023 or 972-2-6271968/9

Open: 8.30am-3pm (sometimes later); services Monday-Wednesday and Friday 7am, Thursday and Saturday 6pm, Sunday 9am. Museum open 9am-12 noon daily (except Sunday) and on request.

Related article:

- Christ the Pantokrator in dome of Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Entrance to Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Joseph Koczera)

- Door to Melkite patriarchate, Jerusalem (Joseph Koczera)

- Road sign near Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Joseph Koczera)

- Bright frescoes and gilded iconostasis in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Gilded iconostasis in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Wedding feast of Cana, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Sts Peter and Paul embracing, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Baptism of Jesus, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Massacre of the Innocents, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Resurrection of Jesus, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Birth of Jesus, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Crucifixion of Jesus, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Yoav Dothan)

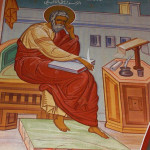

- St John the Evangelist, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Royal Doors in iconostasis of Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Yoav Dothan)

- Jesus among teachers in the Temple, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Jesus entering Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Transfiguration of Jesus, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Jesus raising the widow’s son at Nain, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Burial of Jesus, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Patriarch’s seat in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Dormition of Mary, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Below icons of saints, curtains are drawn over today’s holy people, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- St Matthew the Evangelist, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Jesus at Emmaus, in Melkite church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Yoav Dothan)

- Byzantine monk St Theophanes, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Yoav Dothan)

- Apostles and Old Testament figures in dome of Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Pilate condemning Jesus to death, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Jesus raising Lazarus, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Yoav Dothan)

- Syrian monk St John of Damascus, In Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Yoav Dothan)

- Flight into Egypt, in Melkite Church of the Annunciation, Jerusalem (Yoav Dothan)

References

Anonymous: Griechisch-Katholisch-Melkitisches Patriarchat (Greek Catholic Patriarchate leaflet, undated)

Hilliard, Alison, and Bailey, Betty Jane: Living Stones Pilgrimage: With the Christians of the Holy Land (Cassell, 1999)

Macpherson, Duncan: A Third Millennium Guide to Pilgrimage to the Holy Land (Melisende, 2000)

Martin, George: “The Melkites of Jerusalem” (Catholic Near East, November-December 1995)

External links

Melkite Greek Catholic Church Information Center

Melkite Greek Catholic Patriarchate

Brief video of church interior (YouTube)