Jerusalem

The Kidron Valley, a place of olive groves, ancient tombs and misnamed funerary monuments, divides Jerusalem’s Temple Mount from the Mount of Olives.

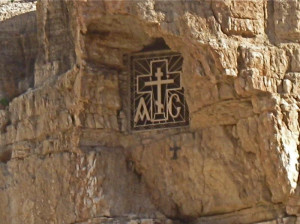

Olive trees in the Kidron Valley, with the Pillar of Absalom in the centre distance (Seetheholyland.net)

Once a deep ravine channelling a seasonal stream, it provided a defensive border to the original City of David — and a route to the wilderness for King David when he fled from his rebellious son Absalom (2 Samuel 15:23).

Jesus often traversed the Kidron on his way to the village of Bethany, his favourite place of rest and refuge.

After the Last Supper, he crossed the valley with his disciples to the garden of Gethsemane. Then, after he was betrayed, he was brought back the same way to the house of the high priest.

By the light of the Passover moon, the whitewashed tombs cut into the valley’s rock-face would have provided a stark reminder to Jesus that on the following day his own body would be laid in a tomb.

Since the 4th century, an identification of the Kidron with the Valley of Jehoshaphat (a name meaning “Yahweh shall judge”) mentioned in the book of Joel (3:2,12) has led to the belief that it will be the place of final judgement.

Valley descends to the Dead Sea

Across the street from the Church of All Nations at Gethsemane, a paved path leads southward to the floor of the Kidron Valley. On the right is the Greek Orthodox Church of St Stephen.

In the northerly direction, the valley continues for 35 kilometres, descending steeply through the Judaean wilderness past Mar Saba monastery to the Dead Sea.

Olive trees give this part of the valley a pastoral character.

On the right looms the wall of the Temple Mount, with the sealed double portals of the Golden Gate standing out. On the left, the world’s largest Jewish cemetery stretches up the Mount of Olives. Further on, the Arab village of Silwan clings to the cliffside.

The cemetery’s location follows the Jewish belief that the long-awaited Messiah will pass through the Golden Gate to begin the resurrection of the dead.

In reaction to this belief, Muslims established a cemetery in front of the gate to block the Messiah’s path — and this may also be why the Ottoman ruler Suleiman the Magnificent sealed the gate in 1541.

During the Second Temple period a high, two-tiered bridge spanned the Kidron Valley from the Temple Mount to the Mount of Olives. Across this bridge on the Day of Atonement each year a goat symbolically bearing the sins of the people — the original scapegoat — was led into the wilderness.

The Golden Gate may have been where Jesus entered the city on Palm Sunday. It was probably also the Beautiful Gate of Acts 3:1-10, where the apostle Peter healed a lame beggar.

Monuments face the Temple Mount

Proceeding along the Kidron Valley, three monuments stand out on the left, each facing towards the Temple Mount. All have been attributed to biblical figures, but they are really tombs of prominent citizens of Jerusalem in the Second Temple period.

In order, they are:

• Pillar of Absalom. The tallest (22 metres) and most ornate of the Kidron Valley monuments, it is hewn out of the limestone rock face, with an elegant pinnacle shaped like a Moroccan tagine cooking pot.

The traditional association with Absalom — who died centuries before it was built — is because this rebellious son of King David erected for himself a memorial pillar in the King’s Valley (2 Samuel 18:18).

In 2003 a Byzantine Greek inscription was found on the south side, naming it the tomb of Zechariah the father of John the Baptist, but the authenticity of this identification is uncertain.

Behind the Pillar of Absalom is a 1st-century burial cave called the Tomb of Jehoshaphat, the fourth king of Judah (who died centuries before it existed). It is notable for the carved triangular pediment above its entrance.

• Tomb of the Sons of Hezir. About 50 metres south of the Pillar of Absalom, this has two Greek Doric columns supporting a frieze with an inscription identifying it as belonging to the priestly family of the Bene Hezir.

A mistaken tradition says it is the tomb of James the Just, the first bishop of Jerusalem, who was thrown off the highest corner of the Temple Mount, then stoned and clubbed to death. In earlier times a chapel in the area honoured this early martyr.

• Tomb of Zechariah. A few metres further south, this freestanding cube carved out of bedrock is decorated on each side with Ionic columns and is topped by a sharply pointed pyramid. Again, the identification is unreliable.

In the time of Jesus, these monuments would have been whitewashed. Perhaps they inspired his outburst: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you are like whitewashed tombs, which on the outside look beautiful, but inside they are full of the bones of the dead and of all kinds of filth.” (Matthew 23:27)

Kidron stream carries sewage

In modern times the Kidron has become one of the most polluted valleys in Israel. The Kidron stream still flows (except in summer), but it now carries most of Jerusalem’s sewage. Fortunately, the stretch near the city is piped underground.

Rubbish dumps also abound in the valley, continuing a practice referred to several times in the Bible. As long ago as seven centuries before Jesus, when King Hezekiah cleansed the Temple, his priests “brought out all the unclean things that they found in the temple of the Lord . . . and the Levites took them and carried them out to the Wadi Kidron” (2 Chronicles 29:16).

In Scripture

King David flees from Absalom: 2 Samuel 15:23

Absalom builds his own monument: 2 Samuel 18:18

Judgement in the Valley of Jehoshaphat: Joel 3:2, 12

Jesus enters the city on Palm Sunday: Matthew 21:1-11

Jesus crosses the Kidron Valley: John 18: 1

Peter heals a lame man at the Beautiful Gate: Acts 3:1-10

- The Tomb of the Sons of Hezir (left) and the Tomb of Zechariah (Seetheholyland.net)

- The Pillar of Absalom in the Kidron Valley (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- The Pillar of Absalom, with the wall of the Temple Mount on the right (Seetheholyland.net)

- The Tomb of Zechariah in the Kidron Valley (Seetheholyland.net)

- The Tomb of the Sons of Hezir, burial place of a priestly family (Seetheholyland.net)

- Olive trees in the Kidron Valley, with the Temple Mount at right (Seetheholyland.net)

- The Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives (Seetheholyland.net)

- The Tomb of Jehoshaphat, behind the Pillar of Absalom (Seetheholyland.net)

- Olive trees in the Kidron Valley, with the Pillar of Absalom in the centre distance (Seetheholyland.net)

- The sealed portals of the Golden Gate in the wall of the Temple Mount (Seetheholyland.net)

- The Arab village of Silwan clinging to the edge of the Kidron Valley (Seetheholyland.net)

- Village of Silwan houses across the Kidron Valley from City of David (Seetheholyland.net)

- Polluted Kidron stream flowing past Mar Saba monastery in the Judaean desert (Seetheholyland.net)

- The path to the Kidron Valley, with the Pillar of Absalom in the centre (Yoav Dothan)

- Tomb of Avshalom from Church of St Mary Magdalene (© Deror Avi)

- Greek Orthodox Church of St Stephen in Kidron Valley (Seetheholyland.net)