Jordan

The “rose-red city” of Petra in southern Jordan, famous for its rock-cut monumental buildings, was once the setting for a thriving Christian community with several significant churches.

An early account tells of Christians in Petra being martyred during the persecution of emperor Diocletian at the beginning of the 4th century, for refusing to offer sacrifice to Roman gods.

Nevertheless, a Christian presence persisted. Bishops from Petra attended Church synods and councils from AD 343, indicating that the city had become a significant Christian centre.

Crosses chiselled into sandstone walls show which large tombs were converted into churches. Then a succession of new churches was built.

The Roman historian Epiphanius mentions that the conversion of Petra’s residents was a slow process throughout the late 4th and 5th centuries.

Then a monk called Mar Sauma arrived with 40 brother monks in AD 423. They found the gates locked against them, but a rainstorm struck with such intensity that part of the city wall was broken, allowing them in. Since the storm had broken a four-year drought, the water-dependent Nabateans saw the event as miraculous and even pagan priests converted to Christianity.

Exotic animals in mosaics

Three churches from the Byzantine era — called the Petra Church, the Blue Chapel and the Ridge Church — have been discovered. They are clustered on the ridge to the north-east of the Colonnaded Street that runs through Petra’s main city area, past the Temple of the Winged Lions.

The large triple-aisled Petra Church, a basilica dedicated to St Mary, was probably the ancient city’s cathedral.

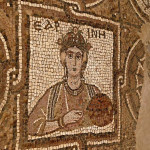

Little of the interior remains except for well-preserved mosaics carpeting the 70-square-metre floors of each of the side aisles. These depict local, exotic and mythological animals, as well as personifications of the Seasons, Ocean, Earth and Wisdom.

The secular nature of these mosaics is probably explained by a reluctance to tread on sacred images.

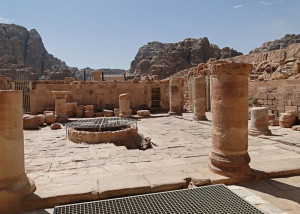

Just west of the church proper is a stone-paved atrium, with a cistern sunk into the centre to catch water. Further west is a baptistery, with a cross-shaped baptismal font.

The basilica was destroyed by a fire, probably in the early 7th century.

Scrolls revealed business deals

The fire that destroyed the Petra Church also carbonised an invaluable hoard of papyrus scrolls cached in a church storeroom. The 152 scrolls — the largest collection of written material from antiquity found in Jordan — lay undiscovered until 1993.

Written mainly in cursive Greek, they have been painstakingly deciphered to reveal details of births, prenuptial arrangements, marriages, business deals, wills, properties disputes and tax responsibilities of about 350 members of the community.

One of the main figures identified in the scrolls is Theodorus, who married his cousin Stephanous in 537, when he was aged about 24. Later ordained a deacon in the Petra diocese, Theodorus was also a successful landowner with extensive business interests.

A son of Theodorus is recorded as being responsible for paying local taxes on a vineyard — at the rate of 47.5 per cent! This affluent family apparently owned much property in the Petra region.

Church overlooked the city

The Ridge Church had a commanding position, with a 360-degree view of the central city, atop the northern slope of the valley in which Petra sits.

The oldest church in the city, dating from the 4th century, it had two side aisles separated from the nave by five columns on each side.

Behind it, city walls across the valley would have protected Petra against invasion from the north.

Between the Petra Church and the Ridge Church is the Blue Chapel, so named after its four blue Egyptian granite columns, topped with Nabataean horned capitals, that collapsed in an 8th-century earthquake but have been re-erected.

The chapel also had blue sandstone flooring and blue marble furnishings — including a blue marble pulpit.

This building is believed to have been converted into a residence and chapel for Petra’s bishop.

Tombs and temples were converted

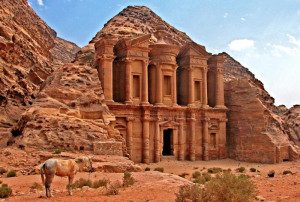

Other buildings converted to Christian churches include the Urn Tomb and al-Deir (Arabic for “the Monastery”).

The Urn Tomb, the first of the four Royal Tombs just north of the amphitheatre, still bears an inscription to “Christ the Saviour” on one of its inside walls.

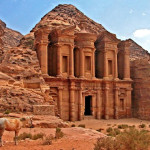

Al-Deir, the biggest and most grandiose monument in Petra, is in the hills overlooking the city from the north-west. A visit involves a walk of about an hour from the city centre, up 800 rock-cut steps.

At 50 metres wide and 45 metres high, it is much bigger than al-Khazneh (“the Treasury”) — the famous monument that appears to visitors arriving through the gorge called the Siq (and in which the climax of the 1989 film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was set).

Originally cut out of the rock to serve as a mortuary temple, al-Deir was apparently later adapted to Christian use. It seems to have acquired its name of the Monastery from the crosses painted and inscribed on its inner walls.

Two Greek monks were recorded as living in the building in 1217.

Petra was in biblical Edom

In biblical times Petra was a city of the Edomites, whose ancestor Esau settled there after he was tricked out of his rightful inheritance by his twin brother Jacob.

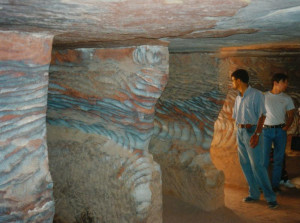

By the middle of the second century BC, the Edomites had been displaced by the Nabataeans. These former nomad herdsmen made Petra their multicoloured sandstone capital city, transforming it into a desert oasis by using ingenious aqueducts and cisterns to conserve water from flash floods.

The Nabataeans also controlled trade routes from Arabia to Mesopotamia and Syria, exacting high tolls from caravans which passed their way.

One tradition has the Three Wise Men buying their gold, myrrh and frankincense at Petra on their way to Bethlehem.

The greatest Nabataean king was Aretas IV (9 BC to AD 40), whose rule extended as far north as Damascus. His daughter Phasaelis was married to Herod Antipas, who divorced her to marry Herodias, his brother’s wife. Aretas IV then marched on Herod’s army, defeated it and captured territories along the West Bank of the Jordan River.

After his conversion, St Paul stays he spent time in “Arabia” (Galatians 1:17) — the name then given to the territory of the Nabateans — where he probably began his commission to preach the Gospel to pagans. It was Aretas IV who was pursuing him when Paul later escaped Damascus by being lowered in a basket from the city wall.

In AD 106 Petra was annexed by the Roman empire. Rome’s diversion of the caravan trade and some devastating earthquakes in subsequent centuries put the city into decline.

Poet recanted his rosy view

From the 13th century Petra was abandoned. It remained forgotten by the Western world until 1812 when a young Swiss explorer, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, disguised as an Arab pilgrim, persuaded a local guide to take him there.

Burckhardt’s published account inspired the English clergyman John William Burgon to write his prize-winning poem Petra, with its line “A rose-red city — half as old as Time!”

The poem, published in 1845, ran to 366 lines — much longer than the extract generally offered in anthologies.

Burgon, who later became dean of Chichester Cathedral, had never visited Petra when he composed his poem. He did so in 1862, describing it in a letter to his sister as “the most astonishing and interesting place I ever visited”. However, perhaps reflecting his ill health at the time, he added: “But there is nothing rosy in Petra by any means.”

Administered by: Petra Development and Tourism Regional Authority

Tel.: +962 (0)3 215-6020 (Visitors’ Centre)

Open: 6am-6pm (4pm in winter)

- Floor mosaics in Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Covered remains of Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Urn Tomb at Petra (Chris Yunker)

- Marble chancel screen at Petra Church (Dennis Jarvis)

- Stone vessel at Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Screen over cistern at Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

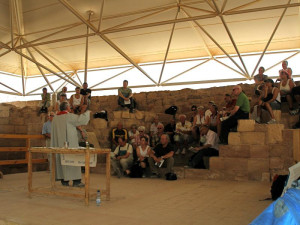

- Pilgrims holding a service in Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Fragments of columns at Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Notice at Petra’s Ridge Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Toppled column drums near Petra’s churches (Seetheholyland.net)

- Colonnaded Street at Petra (Seetheholyland.net)

- Colonnaded Street at Petra (Ana Paula Hirama)

- Baptistery of Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Remains of columns at Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Mosaic personifying Summer in Petra Church (Gustavo Jeronimo)

- Mosaic personifying Spring in Petra Church (Bernard Gagnon)

- Blue Church at Petra (Dennis Jarvis)

- Aisle of mosaics in Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Multicoloured sandstone at Petra (Seetheholyland.net)

- Overview of some of Petra’s monuments (Chris Yunker)

- Pink sandstone cave at Petra (Seetheholyland.net)

- Path to al-Deir (Steve Peterson)

- Carved capitals at Petra Church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Al-Deir, Petra’s biggest monument (Dennis Jarvis)

- Mosaic of wild boar in Petra Church (Bernard Gagnon)

- Mosaic of deer in Petra Church (Luigi Guarino)

- Petra Church atrium and water cistern (Bernard Gagnon)

- Granite columns at Blue Church (David Loong)

References

Basile, Joseph J.: “When People Lived at Petra”, Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 2000

Bikai, Patricia Maynor: “The Churches of Byzantine Petra”, Near Eastern Archaeology, December 2002

Bourbon, Fabio, and Lavagno, Enrico: The Holy Land Archaeological Guide to Israel, Sinai and Jordan (White Star, 2009)

Burckhardt, Johann Ludwig: Travels in Syria and the Holy Land (John Murray, 1822)

Burgon, John William: Petra, a prize poem (Oxford, 1845)

Dyer, Charles H., and Hatteberg, Gregory A.: The New Christian Traveler’s Guide to the Holy Land (Moody, 2006)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gochis, Djinna, and Michaels, Christine: “Mysterious Petra Rediscovered”, Catholic Near East Magazine, fall 1978

Goulburn, Edward Meyrick: John William Burgon, late Dean of Chichester : a biography, volume 1 (J. Murray, 1892)

Milne, Mary K.: “Rose-Red City, Half as Old as Time”, CNEWA World, September/October 2002

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: “What was Paul Doing in ‘Arabia’?”, Bible Review, October 1994

External links

Rose-Red City, Half as Old as Time (CNEWA)

Petra: The Churches (Nabataea.net)