West Bank

The spectacle of the Monastery of St George — a cliff-hanging complex carved into a sheer rock wall in the Judaean Desert, overlooking an unexpectedly lush garden with olive and cypress trees — is one of the most striking sights of the Holy Land.

The monastery’s picturesque setting is in a deep and narrow gorge called Wadi Qelt, in a cliff face pocked with caves and recesses that have offered habitation to monks and hermits for many centuries.

The wadi winds its deep and tortuous course for 35 kilometres between Jerusalem and Jericho — for most of the way providing a route for the Roman road on which Jesus set the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37).

Some also envisage it as the “valley of the shadow of death” in Psalm 23.

The monastery, founded in the 5th century, is about 9 kilometres from Jericho and about 20 kilometres from Jerusalem, and on a favourite trail for hikers.

It is well known for its hospitality and, unlike most Greek Orthodox monasteries, welcomes female pilgrims and visitors — following a precedent set when a Byzantine noblewoman claimed the Virgin Mary had directed her there for healing from an incurable illness.

St George came from Cyprus

The monastery was founded in the 5th century when John of Thebes, an Egyptian, drew together a cluster of five Syrian hermits who had settled around a cave where they believed the prophet Elijah was fed by ravens (1 Kings 17:5-6).

But it is named after its most famous monk, St George of Koziba, who came as a teenager from Cyprus to follow the ascetic life in the Holy Land in the 6th century, after both his parents died.

Another tradition links a large cave above the monastery with St Joachim, father of the Virgin Mary. He is said to have stopped to lament the barrenness of his wife, St Anne — until an angel arrived to tell him she would conceive.

The monastery went through the phases of destruction in the 7th century by the Persians (who martyred all 14 resident monks), rebuilding in the 12th century by the Crusaders, then disuse after the Crusaders were expelled from the Holy Land.

Complete restoration was undertaken by a Greek monk, Callinicos, between 1878 and 1901. The bell tower was added in 1952.

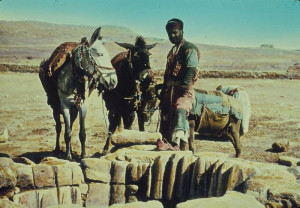

In 2010 a new road improved access, but visitors must walk down a steep and winding path for about 15 minutes (or hire a donkey from local Bedouin) to reach the monastery.

Just a handful of monks remain at St George’s, one of only five monasteries still functioning in the Judaean Desert.

Mosaic floor from 6th century

The three-level monastery complex encompasses two churches, the Church of the Holy Virgin and the Church of St George and St John. They contain a rich array of icons, paintings and mosaics.

In the ornate Church of the Holy Virgin, the principal place of worship, a mosaic pavement depicts the Byzantine double-headed eagle in black, white and red. The royal doors in the centre of the relatively modern iconostasis date from the 12th century.

The Church of St John and St George has a 6th-century mosaic floor. A reliquary contains the skulls of the 14 monks martyred by the Persians, and a glass casket encloses the incorrupt remains of a Romanian monk who died in 1960. A niche contains the tomb of St George.

The monastery also holds the tombs of the five hermits who began the monastery.

Stairs from the inner court of the monastery lead to the cave-church of St Elijah. From this cave, a narrow tunnel provides an escape route to the top of the mountain.

The view from the balcony of the inner court includes Roman aqueducts supported by massive walls on the other side of the wadi.

Administered by: Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem

Tel.: 054 7306557

Open: 9am-1pm; Sunday closed.

- Bridge over Wadi Qelt on way to monastery (© Jerzy Kraj / CTS)

- Fresco of Elijah being fed by ravens (© Stanislao Lee / CTS)

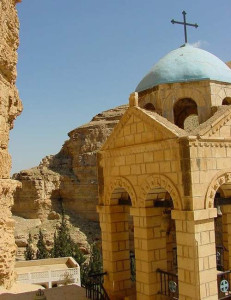

- Entrance to Monastery of St George (© Jerzy Kraj / CTS)

- Monk’s cave, with basket to receive supplies (© Marie-Armelle Beaulieu / CTS)

- Cave-church of St Elijah (© Stanislao Lee / CTS)

- Archway on way to Monastery of St George (Avishai Teicher / PikiWiki Israel)

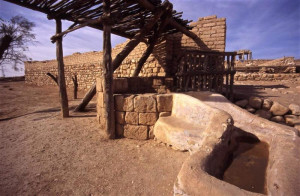

- Aqueduct from spring of Ein Kelt to Jericho (© vizAviz)

- Fertile valley of Wadi Qelt (© Don Schwager)

- Rugged setting of Monastery of St George (Nir Ohad / PikiWiki Israel)

- Close-up view of Monastery of St George (Avishai Teicher / PikiWiki Israel)

- Hospitable Greek Orthodox monk at Monastery of St George (Don Schwager)

- Monastery of St George in Wadi Qelt (Avishai Teicher / PikiWiki Israel)

- Bell tower at Monastery of St George (Don Schwager)

- Aqueduct crossing Wadi Qelt (© vizAviz)

- Wadi Qelt in Judaean Desert (Jerzy Strzelecki)

- Precarious access to monk’s cave in Wadi Qelt (Sir Kiss)

- Abandoned cell being renovated in Wadi Qelt (© vizAviz)

- Lush growth following the Roman aqueduct in Wadi Qelt (B. Hartford J. Strong)

- Monastery of St George carved into sheer rock face (Giora Lev / PikiWiki Israel)

- Monastery bell tower (© Marie-Armelle Beaulieu / CTS)

- View from one of the monastery windows (Don Schwager)

- A cross on the old Roman road pointing the way to the monastery (Don Schwager)

References

Bourbon, Fabio, and Lavagno, Enrico: The Holy Land Archaeological Guide to Israel, Sinai and Jordan (White Star, 2009)

Cohen, Daniel: The Holy Land of Jesus (Doko Media, 2008)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Giroud, Sabri, and others, trans. by Carol Scheller-Doyle and Walid Shomali: Palestine and Palestinians (Alternative Tourism Group, 2008)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Rossing, Daniel: Between Heaven and Earth: Churches and Monasteries of the Holy Land (Penn Publishing, 2012)