West Bank

The Palestinian village of Taybeh, the only Christian town left in Israel or Palestine, holds fast to its memory of Jesus seeking refuge there shortly before his crucifixion.

The Gospel of John says Jesus went to Taybeh — then called Ephraim — after he raised Lazarus to life and the Jewish authorities planned to put Jesus to death.

“Jesus therefore no longer walked about openly among the Jews, but went from there to a town called Ephraim in the region near the wilderness; and he remained there with the disciples.” (John 11:54)

Taybeh (pronounced Tie-bay) is 30 kilometres northeast of Jerusalem and 12 kilometres northeast of Ramallah. From its elevated site between biblical Samaria and Judea, it overlooks the desert wilderness, the Jordan Valley, Jericho and the Dead Sea.

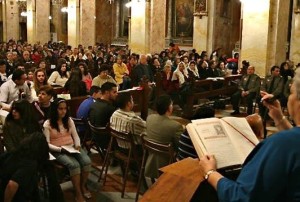

Living amidst Muslim villages, Israeli settlements and military roadblocks, Taybeh’s inhabitants (numbering 1300 in 2010) are intensely proud of their Christian heritage.

The village’s Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic (Latin) and Greek Catholic (Melkite) communities maintain an ecumenical spirit — even celebrating Christmas together on December 25 according to the Western calendar and Easter according to the Eastern calendar.

Patron is St George

The village of Taybeh was first settled by Canaanites about 2500 years before Jesus came to visit. It is mentioned as Ophrah (or Ofrah), a town of the tribe of Benjamin, in Joshua 18:23, and shown on the 6th-century Madaba mosaic map as “Ephron also Ephraia where went the Lord”.

The Muslim sultan Saladin changed the biblical name to Taybeh (meaning “good and kind” in Arabic) around 1187 after he found the inhabitants hospitable and generous.

The villagers regard St George — whose traditional birthplace is Lod, near Tel Aviv airport — as their patron. The Greek Orthodox and Melkite churches are both named in his honour.

They also see the pomegranate as a symbol of the fullness of Jesus’ suffering and Resurrection. This fruit appears as a motif in religious art in Taybeh.

A tradition says Jesus told the villagers a parable relating to this fruit, whose sweet seeds are protected by a bitter membrane. Using this image, Jesus explained that to reach the sweetness of his Resurrection he had to go through the bitterness of death.

Old house illustrates parables

The original Church of St George, built by the Byzantines in the 4th century and rebuilt by the Crusaders in the 12th century, lie in ruins on the eastern outskirts of Taybeh, behind the Melkite church. It is called “El Khader” (Arabic for “the Green One”), a name customarily given to St George.

A wide flight of steps leads up to an entrance portico, nave, two side chapels and a cruciform baptistery with a well-preserved font.

Next to the Greek Orthodox church a 4th-century mosaic depicting birds and flowers has been found. A chapel has been built over the site to protect the mosaic.

In the courtyard of the Roman Catholic church stands a 250-year-old Palestinian house, occupied by a local Christian family until 1974. The entrance is claimed to be 2000 years old, with five religious symbols of that time engraved in the stone façade above the door.

Known as the Parable House, it has rooms on three levels — for the family, for large animals and for smaller animals (who also have an access hole under the old wooden door).

The house and its domestic and agricultural furnishings illustrate the context of many of the parables of Jesus and also offer an insight into how the Nativity cave at Bethlehem may have been configured.

Priest’s retreat is remembered

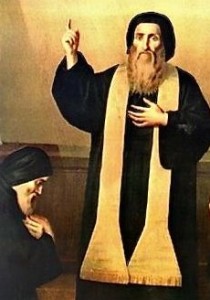

Another celebrated visitor to Taybeh was Charles de Foucauld, a French-born priest, explorer, linguist and hermit who was beatified by the Catholic Church in 2005.

De Foucauld passed through Taybeh as a pilgrim in 1889 and returned in 1898 for an eight-day retreat that is recorded in 45 pages of his spiritual writings.

After his death (he was shot dead by raiding tribesmen in Algeria in 1916, aged 58), his example inspired the founding of several religious congregations.

In 1986 a pilgrims’ hostel called the Charles de Foucauld Pilgrim Centre was opened in Taybeh.

Brewery boosts local economy

Economic and political pressures have forced some 12,000 residents of Taybeh to emigrate to the Americas, Europe and Australia. To ensure jobs for those who remain, the churches and the Taybeh Municipal Council are working to improve the local economy.

A co-operative to sell olive oil, a ceramic workshop to make dove-shaped peace lamps, and a school to train stone-cutters have been established.

More unusually for a region with a 98 per cent Muslim population, an expatriate family returned to Taybeh in 1995 to open the Middle East’s only microbrewery.

Nadim Khoury, who had studied brewing in the United States, opened Taybeh Brewery with his brother David (who became Taybeh’s first democratically-elected mayor in 2005) and their father. Their beer is even brewed under franchise in Germany.

An annual beer festival in October, backed by church and community organisations as well as by diplomatic missions, promotes local products, culture and tourism. The Taybeh Oktoberfest attracts thousands each year, including Christians, Muslims, Jews and overseas visitors from as far away as Japan and Brazil.

To cater for Muslims — who are forbidden to drink alcohol — the brewery has added non-alcoholic beer to its product line.

In Scripture

Jesus goes to Ephraim: John 11:54

Ophrah is named as a town of Benjamin: Joshua 18:23

Tel.: Catholic church 972-2-2958020

Greek Orthodox church 972-2-2898282

Taybeh Municipality: 972-2-2898436

- Living room with stove in Parable House, Taybeh (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Inside Greek Orthodox church, Taybeh (© vizAviz)

- Station of the Cross with Arabic inscription, in Roman Catholic church, Taybeh (Seetheholyland.net)

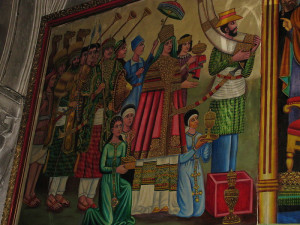

- Raising of Lazarus, in Roman Catholic church, Taybeh (Seetheholyland.net)

- Storage items in Parable House, Taybeh (© vizAviz)

- Pomegranates complementing icon in Catholic church, Taybeh (Seetheholyland.net)

- Door of Parable House, Taybeh, with hole for small animals underneath (Seetheholyland.net)

- Entrance to ruins of St George’s Church, Taybeh (© vizAviz)

- Greek Orthodox church, Taybeh (© vizAviz)

- Entrance to Taybeh Brewery (Magister / Wikimedia)

- Inside Taybeh Brewery (© vizAviz)

- Jesus arriving in Taybeh, mosaic in Roman Catholic church (Seetheholyland.net)

- Charles de Foucauld shrine at Taybeh (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Baptistery in ruins of St George’s Church, Taybeh (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Greek Catholic (Melkite) Church, Taybeh (© vizAviz)

- Steps to ruins of St George’s Church, Taybeh (© vizAviz)

- Christian village of Taybeh (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Roman Catholic church, Taybeh (Seetheholyland.net)

- Ceramic peace lamp in Taybeh (Seetheholyland.net)

- Restoration work in Taybeh (© vizAviz)

- Primitive plough in Parable House, Taybeh (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Deehan, John: “Against the odds”, The Tablet, December 22, 2007

Kalman, Matthew: “Faithful villagers keep it Christian in this last outpost in the Holy Land”, San Francisco Chronicle, December 25, 2005

Levy, Gideon: “Twilight Zone/Taybeh Revisited”, Ha’aretz, July 23, 2010

Shahin, Mariam, and Azar, George: Palestine: A guide (Chastleton Travel, 2005)

External links

Greek Orthodox Church Taybeh

Taybeh Parish (Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem)

The Village of Taybeh (VisitPalestine)

Peace Lamps — Taybeh (Holy Land Artisans)