Eastern Orthodox

Oriental Orthodox

Eastern Catholic

Roman Catholic

Anglican/Protestant/Evangelical

More than a score of Christian churches and denominations have a presence in the Holy Land — not always co-existing in harmony. In fact the scandal of the disunity of Christians is perhaps more evident in the land where the Church began than anywhere else on earth.

In the early centuries, when the Judaeo-Christian Church was still one and undivided, its expansion required organising into geographic units. Bishops of important centres became known as patriarchs — the title accorded Old Testament leaders such as Abraham.

The earliest patriarchates were Antioch (where the name “Christian” was first used), Alexandria and Rome, with Rome (the see of Peter) accorded primacy of honour. Each brought its own culture and traditions to its church-community.

Two more patriarchates, Constantinople and Jerusalem (the “Mother Church”), were later recognised, with Constantinople eventually being accorded second place after Rome. All were Greek-speaking except for Latin-speaking Rome.

Church leaders of East and West at an ecumenical meeting (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

From the 4th century, theological disagreements arose over the nature of Christ. Often exacerbated by political and social tensions, these led the Assyrian Church of the East and what we know as the Oriental Orthodox churches (Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopian, Syriac) to break away. They are still not in communion with either Constantinople or Rome.

In the 11th century, long-standing disputes between the Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) branches of Christianity incited the Great Schism between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism.

From the 16th century, groups within several Oriental and Eastern Orthodox churches re-established communion with the Roman Catholic Church. These became the Eastern Catholic churches.

The 16th century also saw dissent within the Western (Roman) Church spark the Protestant Reformation, resulting in a multitude of new denominations.

The main Christian groupings in the Holy Land today are Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Catholic, Roman (Latin) Catholic and Evangelical or Protestant.

Eastern Orthodox

Greek Orthodox procession in Jerusalem (© Deror Avi)

Greek Orthodox form the largest Christian church in the Holy Land, their patriarch claiming direct descent from St James, the first bishop of Jerusalem.

Leadership in Israel is predominantly expatriate Greek, with married parish clergy and mainly Arab laity (in Jordan and Syria the leadership is largely Arab).

The Greek Orthodox holds major rights to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

The community’s St John the Baptist Church on Christian Quarter Road is one of the oldest in Jerusalem, built originally in the 5th century, and today below street level.

Russian Orthodox pilgrims from Russia visited the Holy Land from the 11th century, but the church did not establish its own institutions in Palestine until the 19th century, when an area now known as the Russian Compound on the Jaffa Road was developed.

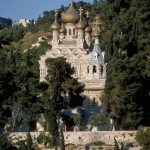

Russian Church of St Mary Magdalene (Seetheholyland.net)

The Russian Revolution of 1917 ended pilgrimages from Russia and also led to a Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, in opposition to the Orthodox Moscow Patriarchate. The two churches signed an act of canonical communion in 2007.

The best-known property of the Church Outside Russia is the onion-domed Church of St Mary Magdalene on the Mount of Olives. The main Moscow Patriarchate church is the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in the Russian Compound.

Romanian Orthodox, with their headquarters in Bucharest, established themselves in Jerusalem in 1935. The interior of their church, St George’s, at 46 Shivtei Israel Street, outside the Old City, is covered with frescoes in neo-Byzantine style.

A small number of clergy look after a big number of Romanian guest workers in Israel.

Oriental Orthodox

Armenian Orthodox ceremony in Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

Armenian Orthodox form the world’s oldest national church, since Armenia was the first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion, in AD 301.

Large numbers came to Jerusalem, where they claim the longest uninterrupted Christian presence. The Armenian Quarter occupies about one-sixth of the Old City.

St James’s Cathedral, in Armenian Orthodox Patriarchate Road, is on the site of the original church built over the place where the Armenians believe the head of the apostle James the Great is buried.

The community holds dearly to the memory of the genocide of more than a million Armenians by Ottoman Turks at the time of the First World War.

Entrance to St Mark’s Syriac Orthodox Church (Seetheholyland.net)

Syriac Orthodox trace their church back to first-century Antioch (in present-day Turkey) and claim the apostle St Peter as their first patriarch in AD 37. Before going to Rome, Peter served seven years in Antioch.

The word “Syriac” is not a geographic indicator, but refers to the use of the Syriac Aramaic language, a dialect of the tongue Jesus spoke in first-century Palestine, in worship.

The Syriac Orthodox (often called “Jacobites”, after an early bishop) believe their St Mark’s Church is on the site of the Last Supper and the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Their Patriarch of Antioch is based in Damascus.

Coptic Orthodox chapel in Church of the Holy Sepuchre (James Emery)

Coptic Orthodox make up the largest Christian church in the Middle East, founded in Alexandria by the evangelist St Mark. Their leader, with the title of pope, is in Egypt. The liturgy is in Coptic, the ancient language of Egypt, with readings in Arabic.

The Jerusalem patriarchate and St Antony’s Church are close to the Ninth Station of the Via Dolorosa. The Coptic Orthodox also have a tiny chapel at the back of the Tomb of Christ in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Ethiopian Orthodox trace their connection to Jerusalem back 1000 years before Christ, when the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba visited King Solomon (1 Kings 10:1-13, 2 Chronicles 9:1-12). She embraced his Jewish faith — and apparently Solomon too, since tradition credits them with a son named Menelik, who became emperor of Ethiopia.

Christianity is believed to have been introduced into Ethiopia by the eunuch finance minister of Queen Candace who came to Jerusalem to worship and was baptised by the apostle Philip (Acts 8:26-40).

Queen of Sheba bringing gifts to Solomon, in Ethiopian Orthodox chapel (© Deror Avi)

The Ethiopian Orthodox retain some Jewish practices, including circumcision, and use freshly-baked bread for Communion.

Their biggest church in Jerusalem is the circular Dabra Gannat Monastery on Ethiopia Street, just off Prophet’s Street. They also occupy two chapels in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and a mud-hut village on its roof.

Eastern Catholic

Greek Catholics, known as Melkites (a word meaning “royalist”), form the second largest Christian church in the Holy Land — after the Greek Orthodox, whose Byzantine liturgy they share. Their Patriarch of Antioch is in Damascus.

Street sign for Greek Catholic Patriarchate Road (Yoav Dothan / Wikimedia)

This Arab church has big numbers in the Galilee region and a small community in Jerusalem.

The fresco-covered patriarchate Church of the Annunciation, inside the Jaffa Gate and up Greek Catholic Patriachate Road, is described in the Living Stones Pilgrimage guidebook as “arguably the most representative Byzantine church in Jerusalem and . . . perhaps the best place to introduce yourself to Orthodox places of worship”.

Within the patriarchate building is a museum of Eastern Church traditions in the Holy Land (open 9am-12pm daily, except Sunday).

Chaldean Catholics separated from the Church of the East (also known as the Nestorian Church) in 1552. Most members are in Iraq (where they are the largest Christian church) and Iran, with a refugee Iraqi community in Jordan and emigrant communities as far away as Australia and New Zealand.

Chaldean Catholic refugees in Jordan (© Tasher Bahoo / Wikimedia)

The patriarchal seat is in Baghdad. In Jerusalem the patriarchal exarchate is at 7 Chaldean Street (off Nablus Road).

Syriac Catholics broke away from the Syriac Orthodox Church and have been in communion with Rome since the 1780s. They also trace their origins to the See of Antioch established by St Peter and retain much of the liturgy (in Aramaic) of their Orthodox counterpart.

Their Patriarch of Antioch is in Beirut. The Jerusalem patriarchal exarchate Church of St Thomas is at 2 Chaldean Street (off Nablus Road).

Armenian Catholics, who separated from the Armenian Orthodox Church, have been in communion with Rome since 1742. They have kept much of the Orthodox liturgy (in classical Armenian) and, like the Armenian Orthodox, suffered in the genocide by Ottoman Turks during the First World War.

Their headquarters is in Bzoummar, Lebanon. The Jerusalem patriarchal exarchate is at the Third Station of the Cross on the Via Dolorosa.

St Maron, who gave the Maronite Catholics their name

Maronite Catholics, the largest Christian community in Lebanon, form the only Eastern church which has always been Roman Catholic, without an Orthodox counterpart.

Founded by St Maron, a 5th-century Syrian hermit, they use Aramaic in their worship and their patriarch is in Beirut. Their membership base in the Holy Land is in Galilee, which is just south of Lebanon.

The patriarchal vicariate is in the Old City on Maronite Convent Road, Jaffa Gate.

Roman Catholic

A Latin patriarchate was established in Jerusalem in 1099, 46 years after the East-West schism, during the Crusades. When the Crusaders were routed 90 years later, the Latin hierarchy fled the Holy Land.

Franciscan friars in a Jerusalem market (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

In 1342 Pope Clement VI gave the custodianship of the holy places to the Franciscan order, whose founder, St Francis of Assisi, had visited the Holy Land in 1219-20.

The brown-robed Franciscans are still a familiar feature of the Holy Land, caring for holy places and active in parishes, schools and social works. Their Custody of the Holy Land is based at St Saviour’s Monastery on St Francis Street, New Gate, where St Saviour’s Church is the only Latin parish church in the Old City. They also retain possession of some chapels in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

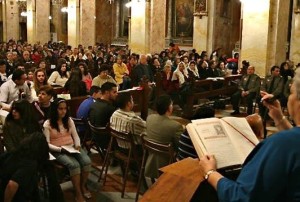

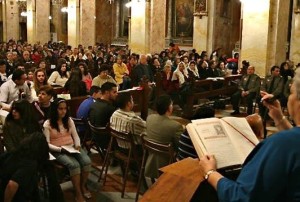

Congregation in St Saviour’s Church (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

About 100 other Roman Catholic religious orders (70 of women and 30 of men) serve in the Holy Land.

In 1847 Pope Pius IX re-established a Latin patriarchate in Jerusalem, with headquarters in Latin Patriarchate Road. Latin-rite Catholics are predominantly Palestinian Arabs (as is the patriarch), though their numbers have been boosted by migrant workers from Asia and Latin America.

Since the mid-1950s there has also been a Hebrew-speaking Catholic community — including convert Jews, Catholic spouses of Jews, and immigrants who have assimilated into the Hebrew-speaking society — which now has its own patriarchal vicar.

Anglican/Protestant/Evangelical

The Anglican and Lutheran churches jointly set up a Jerusalem-based diocese for the Middle East in 1841, though this joint missionary venture ended in 1886. Today both churches have separate bishops (both Palestinian Arabs).

The Anglicans, usually referred to as “Evangelicals” or “Episcopals”, have St George’s Cathedral on Nablus Road, with both Arab and expatriate congregations. St George’s College, a continuing education centre, is within the cathedral compound.

Until the cathedral opened, the bishop’s seat was Christ Church, near the Jaffa Gate in the Old City. The first Protestant church in the Holy Land when it was completed in 1849, it serves Messianic Jews among its charismatic congregation.

Hebrew-inscribed altar in Christ Church (Ian W. Scott)

Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany built the Church of the Redeemer in Muristan Road for the Lutherans and personally dedicated it in 1898.

The church has Arabic, German, English and Danish congregations, and its tall bell tower offers an overview of the Old City.

Several other Reformed churches are established in the Holy Land. They include Baptist, Christian and Missionary Alliance, Christian Brethren, Church of God, Church of the Nazarene, Church of Scotland (Presbyterian), King of Kings Assembly, Pentecostal and Seventh-Day Adventist communities. Most evangelical Protestant churches are not recognised by the state of Israel.

Among those who identify as Jewish there are groups of Messianic Christians whose theology is conservatively evangelical and whose politics is predominantly Zionist, seeing the modern state of Israel as a fulfilment of biblical prophecies.

Related articles:

Inside an Eastern church

The Holy Land’s Christians

How to contact churches in Jerusalem

PHOTO CREDITS: Where the images above are not created by Seetheholyland.net, links to the sources can be found on our Attributions Page.

References

Bailey, Betty Jane and J. Martin: Who Are the Christians in the Middle East? (William B. Eerdmans, 2010)

Bausch, William J.: Pilgrim Church: A Popular History of Catholic Christianity (Twenty-Third Publications, 1993)

Caffulli, Giuseppe: “Jordan’s Christians: A Living Force” (Holy Land Review, Winter 2010)

Cragg, Kenneth: The Arab Christian: A History in the Middle East (Westminster/John Knox, 1991)

Doyle, Stephen: The Pilgrim’s New Guide to the Holy Land (Liturgical Press, 1990)

Eber, Shirley, and O’Sullivan, Kevin: Israel and the Occupied Territories: The Rough Guide (Harrap-Columbus, 1989)

Faris, John D.: “Peter’s First See” (CNEWA World, March-April 2003)

Hilliard, Alison, and Bailey, Betty Jane: Living Stones Pilgrimage: With the Christians of the Holy Land (Cassell, 1999)

McCormick, James R.: Jerusalem and the Holy Land: The first ecumenical pilgrim’s guide (Rhodes & Eaton, 1997)

Macpherson, Duncan (ed.): A Third Millennium Guide to Pilgrimage to the Holy Land (Melisende, 2000)

Marchadour, Alain, and Neuhaus, David: The Land, the Bible and History: Toward the Land That I Will Show You (Fordham University Press, 2007)

Pentin, Edward: “Leading Efforts to Keep Christians in Holy Land” (Holy Land Review, Spring 2009)