Jerusalem

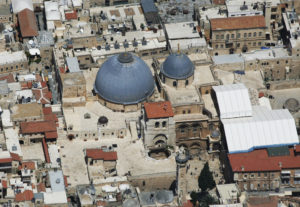

Domes and cropped bell tower of Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Old City of Jerusalem covers what Christians believe is the site of the most important event in human history: The place where Jesus Christ rose from the dead.

But the pilgrim who looks for the hill of Calvary and a tomb cut out of rock in a garden nearby will be disappointed.

• At first sight, the church may bring on a sense of anticlimax. Looking across a hemmed-in square, there is the shabby façade of a dun-coloured, Romanesque basilica with grey domes and a cut-off belfry.

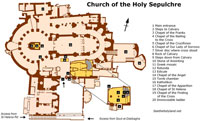

• Inside, there is a bewildering conglomeration of 30-plus chapels and worship spaces. These are encrusted with the devotional ornamentation of several Christian rites.

This sprawling Church of the Holy Sepulchre displays a mish-mash of architectural styles. It bears the scars of fires and earthquakes, deliberate destruction and reconstruction down the centuries. It is often gloomy and usually thronging with noisy visitors.

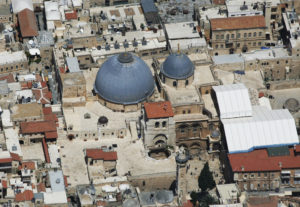

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre from above, huddled in by surrounding buildings (Ilan Arad / Wikimedia)

Yet it remains a living place of worship. Its ancient stones are steeped in prayer, hymns and liturgies. It bustles daily with fervent rounds of incensing and processions.

This is the pre-eminent shrine for Christians, who consider it the holiest place on earth. And it attracts pilgrims by the thousand, all drawn to pay homage to their Saviour, Jesus Christ.

Church replaced pagan temple

Early Christians venerated the site. Then the emperor Hadrian covered it with a pagan temple.

Parvis (courtyard) of Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

Only in AD 326 was the first church begun by the emperor Constantine I. He tore down the pagan temple and had Christ’s tomb cut away from the original hillside. Tradition says his mother, St Helena, found the cross of Christ in a cistern not far from the hill of Calvary.

Constantine’s church was burned by Persians in 614, restored, destroyed by Muslims in 1009 and partially rebuilt. Crusaders completed the reconstruction in 1149. The result is essentially the church that stands today.

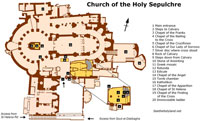

Making sense of the church

Of all the Christian holy places, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is probably the most difficult for pilgrims to come to terms with.

To help make sense of it, this article deals with the church’s major elements and its authenticity. A further article, Church of the Holy Sepulchre chapels, deals with its other devotional areas.

1. The main access to the church, on its south side, is from the Souk el-Dabbagha, a street of shops selling religious souvenirs. Visitors enter the left-hand doorway (the right one was blocked up by Muslim conquerors in the 12th century).

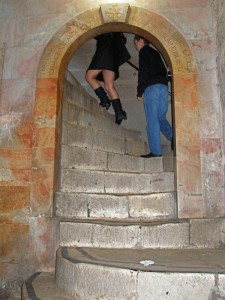

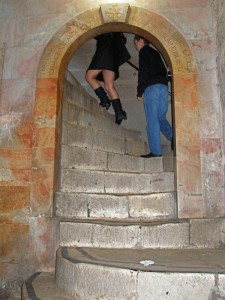

Climbing steps to Calvary (Seetheholyland.net)

2. Instead of following tourists into the often-gloomy interior, immediately turn hard right and ascend a steep and curving flight of stairs. You are now ascending the “hill” of Calvary (from the Latin) or Golgotha (from the Aramaic), both words meaning “place of the skull”. The stairs open on to a floor that is level with the top of the rocky outcrop on which Christ was crucified. It is about 4.5 metres above the ground floor.

3. Immediately on the right is a window looking into a small worship space called the Chapel of the Franks. Here the Tenth Station of the Cross (Jesus is stripped of his garments) is located.

On the floor of Calvary are two chapels side by side, Greek Orthodox on the left, Catholic on the right. They illustrate the vast differences in liturgical decoration between Eastern and Western churches.

4. The Catholic Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross is the site of the Eleventh Station of the Cross (Jesus is nailed to the cross). On its ceiling is a 12th-century medallion of the Ascension of Jesus — the only surviving Crusader mosaic in the building.

Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion (Seetheholyland.net)

5. The much more ornate Greek Chapel of the Crucifixion is the Twelfth Station (Jesus dies on the cross). Standing here, it is easy to understand a little girl’s remark, quoted by the novelist Evelyn Waugh in 1951: “I never knew Our Lord was crucified indoors.”

6. Between the two chapels, a Catholic altar of Our Lady of Sorrows commemorates the Thirteenth Station (Jesus is taken down from the cross).

7. A silver disc beneath the Greek altar marks the place where it is believed the cross stood. The limestone rock of Calvary may be touched through a round hole in the disc. On the right, under glass, can be seen a fissure in the rock. Some believe this was caused by the earthquake at the time Christ died. Others suggest that the rock of Calvary was left standing by quarrymen because it was cracked.

8. Another flight of steep stairs at the left rear of the Greek chapel leads back to the ground floor.

9. To the left is the Stone of Anointing, a slab of reddish stone flanked by candlesticks and overhung by a row of eight lamps.

Stone of Anointing from above (Seetheholyland.net)

Kneeling pilgrims kiss it with great reverence, although this is not the stone on which Christ’s body was anointed. This devotion is recorded only since the 12th century. The present stone dates from 1810.

10. On the wall behind the stone is a Greek mosaic depicting (from right to left) Christ being taken down from the cross, his body being prepared for burial, and his body being taken to the tomb.

11. Continuing away from Calvary, the Rotunda of the church opens up on the right, surrounded by massive pillars and surmounted by a huge dome. Its outer walls date back to the emperor Constantine’s original basilica built in the 4th century. The dome is decorated with a starburst of tongues of light, with 12 rays representing the apostles.

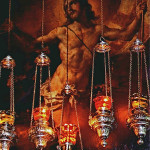

12. In the centre is a stone edicule (“little house”), its entrance flanked by rows of huge candles. This is the Tomb of Christ, the Fourteenth Station of the Cross.

This stone monument encloses the tomb (sepulchre) where it is believed Jesus Christ lay buried for three days — and where he rose from the dead. A high-tech photogrammetric survey late in the 20th century showed that the present edicule contains the remains of three previous structures, each encasing the previous one, like a set of Russian dolls.

The Edicule after restoration in 2017 (Ben Gray / ELCJHL)

13. At busy times, Greek Orthodox priests control admission to the edicule. Inside there are two chambers. In the outer one, known as the Chapel of the Angel, stands a pedestal containing what is believed to be a piece of the rolling stone used to close the tomb.

14. A very low doorway leads to the tomb chamber, lined with marble and hung with holy pictures. On the right, a marble slab covers the rock bench on which the body of Jesus lay. It is this slab which is venerated by pilgrims, who customarily place religious objects and souvenirs on it.

The slab was deliberately split by order of the Franciscan custos (guardian) of the Holy Land in 1555, lest Ottoman Turks should steal such a fine piece of marble.

An agreement between the major Christian communities at the church enabled work to begin in May 2016 to reinforce and restore the edicule. The work was undertaken by a team of scientists from the National Technical University of Athens.

Inside the restored tomb chamber, with the window exposing the rock wall of the burial cave at left (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

In October 2016 the team removed the marble slab, exposing a layer of fill material covering another slab of marble with a small Crusader cross etched on it. Beneath it was the bench on which the body of Jesus lay.

When the team restored the marble cladding and resealed the burial bed, they also cut a small window into the southern interior wall of the shrine to expose one of the limestone walls of the burial cave.

The multi-million-dollar restoration was completed in March 2017. The reddish-cream marble of the edicule emerged cleaned of centuries of grime, dust and soot from candle smoke, and freed from a grid of iron girders that had held it together since 1947.

But scientists warned that even more work would be necessary to shore up the unstable foundations of the shrine and the surrounding rotunda to avoid the risk of collapse. This was undertaken during a two-year project to restore and conserve the pavement stones inside the church that began in March 2022.

Three denominations share ownership

Ownership of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is shared between the Greek Orthodox, Catholics (known in the Holy Land as Latins) and Armenian Orthodox.

The Greeks (who call the basilica the Anastasis, or Church of the Resurrection) own its central worship space, known as the Katholikon or Greek choir. The Armenians own the underground Chapel of St Helena which they have renamed in honour of St Gregory the Illuminator.

Katholikon (or Greek choir), the central worship space in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

The Catholics own the Franciscan Chapel of the Apparition (which commemorates the tradition that the risen Christ first appeared to his Mother) and the deep underground Chapel of the Finding of the Cross.

Three minor Orthodox communities, Coptic, Syriac and Ethiopian, have rights to use certain areas. The Ethiopian monks live in a kind of African village on the roof, called Deir es-Sultan.

The rights of possession and use are spelt out by a decree, called the Status Quo, originally imposed by the Ottoman Turks in 1757. It even gives two Muslim families the sole right to hold the key and open and close the church — a tradition that dates back much further, to 1246.

Ladder symbolises Status Quo

Each religious community guards its rights jealously. The often-uneasy relationship laid down by the Status Quo is typified by a wooden ladder resting on a cornice above the main entrance and leaning against a window ledge.

Chapel of the Finding of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

The ladder has been there so long that nobody knows how it got there. Various suggestions have been offered: It was left behind by a careless mason or window-cleaner; it had been used to supply food to Armenian monks locked in the church by the Turks; it had served to let the Armenians use the cornice as a balcony to get fresh air and sunshine rather than leave the church and pay an Ottoman tax to re-enter it.

The ladder appears in an engraving of the church dated 1728, and it was mentioned in the 1757 edict by Sultan Abdul Hamid I that became the basis for the Status Quo.

Immovable ladder on ledge over entrance to Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

It would be too much to expect that the ladder seen today has resisted the elements since early in the 18th century. In fact the original has been replaced at least once.

In 1997 the ladder suddenly disappeared for some weeks, after a Protestant prankster hid it behind an altar. When it was discovered and returned, a steel grate was installed over the lower parts of both windows above the entrance. And in 2009 the ladder mysteriously appeared against the left window for a day.

The ladder, window and cornice are all in the possession of the Armenian Orthodox. And because the ladder was on the cornice when the Status Quo began in 1757, it must remain there.

Archaeology supports authenticity

Visitors may easily be disillusioned by the church’s contrasting architectural styles, its pious ornamentation and its competing liturgies.

If these man-made elements could be removed, as biblical scholar John J. Kilgallen has written, “we would stand between two places not more than 30 yards [90 feet] apart, with dirt and rock and grass under our feet and the open air all around us. Such was the original state of this area before Jesus died and was buried here.”

Inside the Tomb of Christ (© Adriatikus)

But is this the place where Christ died and was buried? “Very probably, Yes,” declares biblical scholar Jerome Murphy-O’Connor in his Oxford Archaeological Guide The Holy Land. Eusebius, the first Church historian (in the 4th century), says the site was venerated by the early Christian community.

And the Israeli scholar Dan Bahat, former city archaeologist of Jerusalem, says: “We may not be absolutely certain that the site of the Holy Sepulchre Church is the site of Jesus’ burial, but we have no other site that can lay a claim nearly as weighty, and we really have no reason to reject the authenticity of the site.”

One major objection raised is that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is inside the city walls, while the Gospels say the crucifixion took place outside. Archaeologists have confirmed that the site of the church was outside the city until about 10 years after Christ’s death, when a new wall was built.

In 2025 archaeobotanical and pollen analysis on samples retrieved from excavations under the floor of the basilica revealed the presence of olive trees and grapevines from the pre-Christian era — mirroring the description of the area in the Gospel of John (19:41): “Now there was a garden in the place where he was crucified . . . .”

Some favour a competing site, the Garden Tomb. Though it offers a more serene environment, the tombs in its area predate the time of Christ by several centuries.

Further article:

Church of the Holy Sepulchre chapels, dealing with the other devotional areas.

In Scripture:

The crucifixion: Matthew 27:27-56; Mark 15:16-41; Luke 23:26-49; John 19:16-37

The burial of Jesus: Matthew 27:57-66; Mark 15:42-47; Luke 23:50-56; John 19:38-42

The Resurrection: Matthew 28:1-10; Mark 16:1-8; Luke 24:1-12; John 20:1-10

Administered by: Confraternity of the Holy Sepulchre (Greek Orthodox), Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land (Catholic), Brotherhood of St James (Armenian Orthodox)

Tel.: 972-2-6267000

Opens: Apr-Sep 4am, Oct-Mar 5am. Closes: Apr-Aug 8pm, Mar and Sep 7.30pm, Oct-Feb 7pm. Sunday morning liturgies are usually: Coptic 4am, Catholic 5.30am, Greek Orthodox 7am, Syriac Orthodox 8am; Armenian Orthodox 8.45am on alternating Sundays with a weekly procession at 4.15pm.

-

-

Domes and cropped bell tower of Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Bell tower of Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre from above, huddled in by surrounding buildings (Ilan Arad / Wikimedia)

-

-

Steps down to Church of the Holy Sepulchre from St Helena Rd entrance (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Entrance to Church of the Holy Sepulchre from Souk el-Dabbagha (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Parvis (courtyard) of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Pilgrims and tourists gather in front of Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Only entrance into the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Climbing steps to Calvary (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Mosaic in Catholic Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Twelfth Station: Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion Twelfth Station: Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Close-up of crucifix in Chapel of the Crucifixion (Picturesfree.org)

-

-

Pilgrims queue to touch rock of Calvary in Chapel of the Crucifixion (Berthold Werner)

-

-

Disc marking traditional place where Jesus’ cross stood, in Chapel of the Crucifixion (Adriatikus)

-

-

Looking from Calvary to the dome over the Katholikon (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Catholic altar of Our Lady of Sorrows (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Fissure in rock of Calvary, in Chapel of the Crucifixion (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Steps down from the floor of Calvary (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Christ taken down from the cross, detail of mosaic at the Stone of Anointing (Rachel Ricci)

-

-

Christ carried to tomb, detail of mosaic at Stone of Anointing (Rachel Ricci)

-

-

Christ laid out for anointing, detail of mosaic at Stone of Anointing (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Pilgrims at the Stone of Anointing (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Stone of Anointing from above (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Part of the rotunda in Church of the Holy Sepulchre (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

The Edicule after restoration in 2017 (Ben Gray / ELCJHL)

-

-

Holy Thursday Eucharist at the Tomb of Jesus (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Lighting candles on girder that braced the Tomb of Christ before restoration in 2017 (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Back view of edicule over the Tomb of Christ (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Dome over the Tomb of Christ (© Deror Avi)

-

-

Light from opening in dome above Tomb of Christ (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Sunburst design in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre dome (Susie Cagle)

-

-

Edicule over Tomb of Christ with doors shut (Dainis Matisons)

-

-

Crowd waits to enter the Tomb of Christ (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Front of edicule over the Tomb of Christ (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Visitors entering the Tomb of Christ (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Entrance to the Chapel of the Angel, with the tomb chamber beyond the pedestal with candles (Diego Delso / Wikimedia)

-

-

Rolling-stone tomb similar to the one in which Jesus was buried (Biblicalisraeltours.com)

-

-

Figure of the crucified Christ in the tomb on Good Friday (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Inside the Tomb of Christ (Adriatikus)

-

-

Close-up of the split in the marble slab over the bench where Jesus’ body lay (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Decorations inside the Tomb of Christ (Picturesfree.org)

-

-

Pilgrim leaving the tomb chamber (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Lamps and medallions on the front of the Tomb of Christ (Susie Cagle)

-

-

The resurrected Christ, a painting hanging above the entrance to the edicule (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Katholikon (or Greek choir), the central worship space in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Greek Orthodox clergy at altar in the Katholikon (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Icon of Jesus in dome of the Katholicon (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Service in front of the edicule (James Emery)

-

-

Chapel of the Apparition of Jesus to his Mother (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Steps down to Chapel of St Helena and Chapel of the Finding of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Noah’s Ark mosaic in floor of Chapel of St Helena (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Visitors in Chapel of St Vartan (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Drawing of a ship, possibly by a pilgrim, in Chapel of St Vartan (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Chapel of the Finding of the Cross (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Statue of St Helena with the True Cross, in Chapel of the Finding of the Cross (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Rooftop view of Church of the Holy Sepulchre’s Katholikon dome (Berthold Werner)

-

-

Ethiopian Orthodox monks’ village on roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Members of Ethiopian Orthodox community at lunch on roof of Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Dome of the Katholikon and dome of Chapel of St Helena (right), from roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Sword, spurs and cross of Godfrey of Bouillon, Crusader who became first ruler of Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1099, in Latin sacristy in Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Immovable ladder on ledge over entrance to Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Prankster removing Holy Sepulchre ladder in 1997 (Silencedogood97)

-

-

The domes and cropped bell tower of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Key to Church of the Holy Sepulchre (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Chapel of St Helena, now dedicated to St Gregory the Illuminator, with floor restored in 2017 (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Front of edicule over the Tomb of Christ (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

ide of the edicule, showing reddish-cream marble restored in 2017 (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Top of edicule, below the dome’s starburst of 12 rays of light representing the apostles (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

The ornately furnished facade of the edicule (Fiona Wilson-Taylor / Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

The Holy Sepulchre dome towering over the edicule containing the Tomb of Christ (Fiona Wilson-Taylor / Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

The edicule containing the Tomb of Jesus (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands amidst an untidy clutter of roofs with television discs, solar panels and water tanks (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Restored paintings of holy people over the steps to the lower chapels in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Late at night, oil lamps on the front of the edicule are topped up. (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

A Muslim keyholder prepares to lock the Holy Sepulchre door (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

A Muslim keyholder locks the Holy Sepulchre door (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

A Greek Orthodox priest in the doorway of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

References:

Bahat, Dan: “Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?” (Biblical Archaeology Review, May-June 1986)

Bar-Am, Aviva: Beyond the Walls: Churches of Jerusalem (Ahva Press, 1998)

Benelli, Carla, and Saltini, Tommaso (eds): The Holy Sepulchre: The Pilgrim’s New Guide (Franciscan Printing Press, 2011).

Charlesworth, James H.: The Millennium Guide for Pilgrims to the Holy Land (BIBAL Press, 2000)

Cohen, Raymond: Saving the Holy Sepulchre: How Rival Christians Came Together to Rescue their Holiest Shrine (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Hadid, Diaa: “Risk of Collapse at Jesus’ Tomb Unites Rival Christians” (New York Times, April 6, 2016)

Herman, Danny: “Who Moved the Ladder?” (Biblical Archaeology Review, January/February 2010).

Kilgallen, John J.: A New Testament Guide to the Holy Land (Loyola Press, 1998)

Mackowski, Richard M.: Jerusalem: City of Jesus (William B. Eerdmans, 1980)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Notley, R. Steven: Jerusalem: City of the Great King (Carta Jerusalem, 2015)

Powers, Tom: “The Church of the Holy Sepulchre: Some perspectives from history, geography, architecture, archaeology and the New Testament” (Artifax, Autumn 2004-Spring 2005)

Prag, Kay: Jerusalem: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 1989)

Simmermacher, Günther: The Holy Land Trek: A Pilgrim’s Guide (Southern Cross Books, 2012).

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

Waugh, Evelyn: “The Plight of the Holy Places” (Life, December 24, 1951.

Wright, J. Robert: “Holy Sepulchre” (Holy Land, spring 1998)

External links: