Egypt

The Gospel account of the Holy Family seeking refuge in Egypt is unsupported by archaeological evidence, but to Coptic Christians it is affirmed by their oral tradition, a fifth-century patriarch’s vision, the locations of early desert monasteries — and the claimed confirmation of modern-day apparitions.

Only Matthew’s Gospel records that Joseph, Mary and Jesus fled to Egypt to escape King Herod’s massacre of young children. In a few short paragraphs, Joseph is warned in dreams to leave Bethlehem and later, when Herod dies, to return to Israel (2:13-23).

Holy Family arriving in Egypt, by Edwin Longsden Long (Wikimedia)

Egypt was a logical refuge. It was part of the Roman empire, but outside Herod’s domain, and some cities had significant Jewish communities. The well-trodden Via Maris (“way of the sea”) through Gaza and the northern Sinai coast made travel easy and relatively safe.

Biblical scholars W. F. Albright and C. S. Mann affirm that “there is no reason to doubt the historicity of the story of the family’s flight into Egypt. The Old Testament abounds in references to individuals and families taking refuge in Egypt, in flight either from persecution or revenge, or in the face of economic pressure.”

Major source inspired by vision

Outside of the New Testament, in the second century the anti-Christian Greek philosopher Celsus accused Jesus of “having worked for hire in Egypt on account of his poverty, and having experimented there with some magical powers, in which the Egyptians take great pride”.

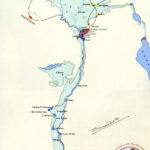

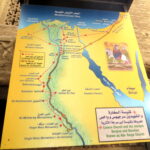

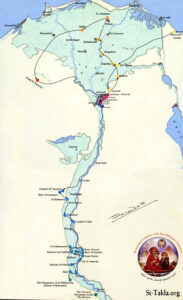

Map of Holy Family’s itinerary signed by Coptic Pope Shenouda III (Orthodox Wiki)

In the third century the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt was noted by the theologian Hippolytus of Rome, who even gave a time frame of three and a half years.

A major source for the Coptic Orthodox Church is a homily attributed to the fifth-century Coptic Pope Theophilus, 23rd Patriarch of Alexandria, and said to be inspired by a vision of the Virgin Mary. He described the Holy Family fleeing from the Milk Grotto in Bethlehem and detailed numerous miracles performed by Jesus in the towns of Lower and Upper Egypt.

Some accounts say that Salome, possibly a relative of Mary (and often mistakenly referred to as her midwife) accompanied the family.

Miracles or fantasies?

The Arabic Infancy Gospel, from the fifth or sixth centuries, narrates supposed incidents from the family’s travels in the land of the pharaohs — including several miracles, often fantastical, wrought by the child Jesus.

In this account, trees bowed before the infant, animals paid homage to him, pagan idols tumbled at his approach, spiders weaved a thick web to conceal Mary and Jesus in a tree, and there was even a chance encounter with the two criminals who would be crucified alongside Jesus.

List of locations keeps growing

How long the family was in Egypt, where they went or what they did there, is not reported in Matthew’s Gospel. But by the eighth century, building on local traditions, Bishop Zacharias of Sakha had already established a Holy Family path in the Nile Delta.

In the 12th century a scribe called John ibn Said al-Kulzumi drew up a geographical list of nine sites visited by the holy refugees. A century later, when the Coptic priest Abu l-Makarim referred to 14 locations, the outline of an itinerary had clearly been established.

The presence of early monasteries and churches was seen as confirming local traditions, which were also celebrated in Coptic liturgies and art.

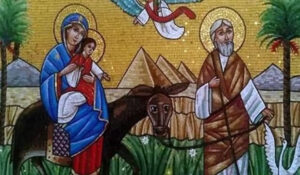

Government mosaic commemorating Holy Family’s visit (State Information Service of Egypt)

A patriarchal commission of hierarchs and scholars has published an “official” map of the route of the Holy Family, but the popular list of holy locations keeps growing, sometimes stirring rivalry between adjacent sites.

With an eye on boosting “spiritual tourism”, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities for Egypt (a predominantly Sunni Muslim state) has launched the Holy Family Trail — a 3220-kilometre route for four-wheel drive adventurers.

Promoters of the trail display unexpected precision: “The Holy Family arrived in Egypt on the 24th day of the Coptic month of Pshnece, or on 2 June . . . . They stayed in Egypt for three years and 11 months,” according to former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs Zahi Hawass.

Nile was crossed and re-crossed

The popular list of locations suggests the Holy Family — travelling by foot, donkey or boat, and moving often — crossed and re-crossed the forks of the Nile Delta, then travelled south (upstream) as far as Gebel Qussqam, before returning by boat down the Nile to the Cairo area and retracing their steps overland to Israel.

Some of the best-attested sites, with their associated Coptic traditions, include:

Bubastis: After arriving through the customary entry point of El-Farama — following in the footsteps of Abraham and Jacob — the Holy Family came to the city of Bubastis in the eastern Nile delta, a centre of worship for the cat goddess Bastet.

Ruins of Bubastis (Einsamer Schütze / Wikimedia)

Coptic tradition says the arrival of the infant Jesus caused a temple’s foundations to shake and all the idols to fall on their faces — echoing Isaiah’s prophecy that “the idols of Egypt will tremble at his presence” (19:1). A field of fallen idols remained in modern times in the ruins of Bubastis, now within the modern city of Zagazig.

Mostorod: In this city, now part of greater Cairo, Mary needed to bathe her son and wash his dusty clothes. Jesus extended his hand to bless the place and a spring of water arose where a well beside the Virgin Mary Church remains.

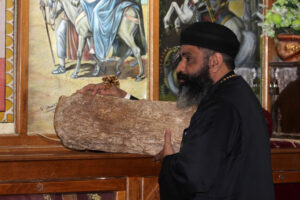

Granite bowl at Samunnud believed to have been used by Mary (© Blessedegypt.com)

Belbeis: As they entered the town, the Holy Family met the funeral procession of a widow’s son. Foreshadowing the miracle at Nain in Luke 7:11-17, the infant Jesus raised the dead man to life.

Samannud: Backtracking north-west, the family crossed the Nile at Samannud. Here Mary baked bread and the Coptic community displays a large granite bowl she is said to have used.

Sakha: In this town near the centre of the Nile Delta, tradition says Jesus left a footprint on a rock. Rediscovered in 1984, the rock was authenticated by Coptic Pope Shenouda III and several miracles have been attributed to it.

Rock at Sakha on which Jesus is believed to have left a footprint (© Blessedegypt.com)

Wadi El Natrun: Travelling through this long valley in the Western Desert, 24 metres below sea level, the family were approached by two lions. With a wave of his hand, Jesus told them to leave and, bowing their heads, they obeyed. The holy infant also caused a sweet-water well to open up among lakes saturated with natron salt. From the third century the Wadi El Natrun desert attracted thousands of hermits, and it remains the most important centre of Coptic monasticism.

El Matareya: Leaving the desert behind, the Holy Family crossed to the eastern bank of the Nile and headed for the ancient city of Heliopolis, now El Matareya — a name thought to have come from the Latin word “Mater” in recognition of Mary’s presence. On the way they would have passed the pyramids of Giza, built 2500 years earlier.

Heliopolis as envisaged by early 20th-century German landscape painter Carl Wuttke (Wikimedia)

At Heliopolis they lived in the Ain Shams neighbourhood, where there was a large Jewish community. According to one tradition, two brigands pursued the family but a fig tree opened its trunk to conceal them.

Zeitoun: Coptic tradition says Mary was so exhausted from fleeing Herod’s soldiers that she had to stop at Zeitoun, in Old Cairo, for several hours to rest. Mary is also believed to have promised a farmer at nearby Klot Bey that her son would bless his farm so that melons sown on one day could be harvested the next day.

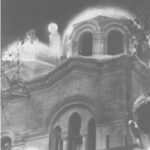

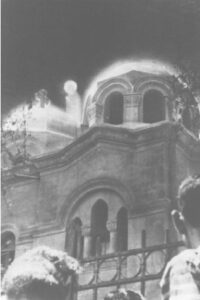

Photograph of an apparition taken on April 9, 1968, by architectural engineer Fawzi Mansour at St Mary’s Church, Zeitoun

Zeitoun attracted international attention when apparitions of Mary were seen on the roof of the Church of the Holy Virgin during a period of about three years from April 2, 1968.

The visions were pronounced authentic by the Coptic Orthodox Church and a statement from the Muslim government declared: “Official investigations have been carried out with the result that it has been considered an undeniable fact that the Blessed Virgin Mary has been appearing on Zeitoun Church in a clear and bright luminous body seen by all present in front of the church, whether Christians or Muslims.”

Babylon Fortress: Joseph is believed to have worked at this Roman fortress in Old Cairo to support his family, who lived in a cave that is now the crypt of the 11th-century Church of St Sergius and St Bacchus (known locally as the Abu Serga Church). The cave, within the walls of the fortress, floods when the level of the Nile are high. Tradition marks the area as the place where the baby Moses was discovered by the pharaoh’s daughter (Exodus 2:3-5). The church also has a well believed to have been used by the Holy Family.

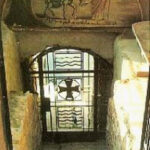

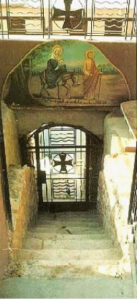

Stone steps in Church of the Virgin, Maadi, believed to have been used by the Holy Family to descend to the Nile (John Sanidopoulos)

Maadi: Moving south, the Holy Family reached Maadi, now a leafy suburb of Cairo but then home to a large Jewish community, and boarded a papyrus felucca sailboat to take them up the Nile towards southern Egypt. The stone steps they used to reach the river are still accessible to pilgrims through the Virgin Mary Church.

Ishnin al-Nasara: On reaching this village, the infant Jesus felt thirsty. There was a well but the water level was too low. His mother took his finger and held it over the well, which then rose to the top. (A rival tradition locates this event at nearby Al-Bahnasa.)

Deir Al-Garnous: Here, where the family rested for four days, Jesus is said to have left a well with water that not only cured every disease but foretold the height of the Nile’s annual inundation.

Gabal Al-Teir: The Holy Family crossed the Nile to use a cave at Gabal Al-Teir, a nesting place for thousands of birds. As their boat passed a cliff, a rock threatened to fall on them but Jesus held it back, leaving his handprint on the rock. (When Almeric, King of Jerusalem, invaded Upper Egypt in the 12th century he is reported to have had the rock chiselled out and taken with him.)

Crypt in Abu Serga Church, Cairo, where the Holy Family is believed to have lived (© Günther Simmermacher)

El Ashmunein: On arrival, according to the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, the family did not know anyone from whom they could seek hospitality, so they went into a temple with 355 idols. All the idols prostrated themselves on the ground. When the governor saw what had happened, he said: “Unless this were the God of our gods, our gods would not have fallen on their faces before him; nor would they be lying prostrate in his presence . . . .” and “all the people of that same city believed in the Lord God through Jesus Christ”. The fifth-century historian Sozomenos said there was a tree in the town that bowed to the ground to worship Jesus.

Deir Abū Hinnis: Just outside this Christian village is Kim Maria (“hill of Mary”) where Mary is believed to have rested. Sixth-century wall paintings by monks in a cave church nearby include perhaps the earliest illustrations of the flight into Egypt.

El–Qusiya: This town (formerly called Cusae or Qesy) has the reputation of not only being visited by the Holy Family but also of being cursed by the infant Jesus. According to Theophilus, this happened after idols fell down when the family arrived, the pagan priests told the family to leave, and townspeople chased them away with rods and axes.

Gebel (Mount) Qussqam: Coptic tradition says the Holy Family’s longest stay in one place was in a cave at Mount Qussqam, 1942 kilometres south of Cairo — and precisely dates its duration on the Coptic calendar from the 7th of Barmoudah to the 6th of Babah, a period of 185 days. It was here that an angel revealed to Joseph that Herod was dead and it was safe to return to Israel, fulfilling Hosea’s prophecy “Out of Egypt I called my Son” (11:1). And it was here that Theophilus received his vision of the family’s travels. Around the cave spreads the fortress-like Monastery of the Holy Virgin of Al-Muharraq.

Monastery of the Virgin in Durunka (Landious Travel)

Durunka: A rival view maintains that the Holy Family travelled 50 kilometres further south to get on a sailboat for their return down the Nile. Here the massive Virgin Mary Monastery of Durunka stands 100 metres high on a mountain side above the Nile Valley. Though no ancient text suggests Durunka as a Holy Family site, Coptic studies expert Otto Meinardus explains that the local bishop began to promote it as such from the 1950s after the Al-Muharraq monastery was riven by internal disputes. Business interests backed the development of the site and it has became a major venue attracting a million pilgrims and tourists a year.

In Scripture:

Joseph is warned to flee to Egypt: Matthew 2:13-15

Joseph is told to return to Israel: Matthew 2:19-23

- Holy Family arriving in Egypt, by Edwin Longsden Long (Wikimedia)

- Map of Holy Family’s itinerary signed by Coptic Pope Shenouda III (Orthodox Wiki)

- Government mosaic commemorating Holy Family’s visit (State Information Service of Egypt)

- Ruins of Bubastis (Einsamer Schütze / Wikimedia)

- Granite bowl at Samunnud believed to have been used by Mary (© Blessedegypt.com)

- Rock at Sakha on which Jesus is believed to have left a footprint (© Blessedegypt.com)

- Heliopolis as envisaged by early 20th-century German landscape painter Carl Wuttke (Wikimedia)

- Monastery of the Syriacs in Wadi el Natrun (Religion Wiki)

- Monastery of St Bishoy, Wadi Natrun (Berthold Werner / Wikimedia)

- Route of the Holy Family mapped out at Abu Serga Church, Cairo (© Günther Simmermacher)

- Coptic Pope Shenouda III of Alexandria, who authenticated a rock believed to have Jesus’ footprint (Orthodox Wiki)

- Photograph of an apparition taken on April 9, 1968, by architectural engineer Fawzi Mansour at St Mary’s Church, Zeitoun

- Remains of Babylon Fortress, Cairo (Jean Robert Thibault)

- Relief of Flight Into Egypt, above entrance to Abu Serga Church, Cairo (© Günther Simmermacher)

- Interior of Abu Serga Church, Cairo (© Günther Simmermacher)

- Entrance to the cavern under the Abu Serga Church where the Holy Family is believed to have stayed (Local’s Guide to Egypt)

- Crypt in Abu Serga Church (© Günther Simmermacher)

- Well from which the Holy Family is believed to have drunk, In Abu Serga Church, Cairo (Ahmed Yousry Mahfouz / Wikimedia)

- Stone steps in Church of the Virgin, Maadi, believed to have been used by the Holy Family to descend to the Nile (John Sanidopoulos)

- Holy Family in stained glass at St John’s Church, Maadi (Stephen Sizer / Wikimedia)

- Flight into Egypt carved into Mokattam Mountain at St Simon the Tanner Monastery, Cairo (© Günther Simmermacher)

- Monastery of the Virgin in Durunka (Landious Travel)

- Return from the Flight into Egypt, by 17th-century Persian artist Mohammad Zaman (Harvard Art Museums / Wikimedia)

References:

Albright, W. F., and Mann, C. S.: Matthew (The Anchor Bible Commentaries Series, 1971)

Curtin, D. P.: Vision of Theophilus: The Flight of the Holy Family into Egypt (Dalcassian Publishing Company, 2023)

Davies, Stevan: The Infancy Gospels of Jesus (Skylight Paths, 2009)

Gabra, Gawdat (ed.): Be Thou There: The Holy Family’s Journey in Egypt (American University in Cairo Press, 2001)

Hawass, Zahi: “The Holy Family in Egypt” (Al-Ahram Weekly, January 3, 2023)

Meinardus, Otto F. A.: The Holy Family in Egypt (American University in Cairo Press, 1987)

Perry, Paul: Jesus in Egypt (Ballantine Books, 2003)

External links: