Jerusalem

The oldest intact church in Jerusalem is the little-known Church of St John the Baptist in the Muristan market of the Old City. It was erected around 1070, some 80 years before the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was rebuilt in its present form, and its crypt dates back to the fifth century.

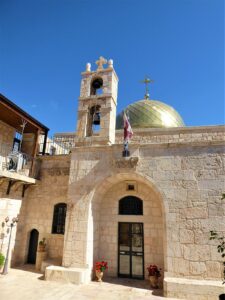

Golden dome of Church of St John the Baptist peeps over Muristan roofs (Seetheholyland.net)

Almost hidden in plain sight, the church’s golden dome peeps above Muristan roofs but its entrance is difficult to find. Its little iron door is nestled between shops at 113 Christian Quarter Road, under a relief of disciples carrying the head of St John the Baptist and a sign in Greek.

This Greek Orthodox church is dedicated to the memory of the beheading of the Baptiser. It should not be confused with the Catholic church of the same name at Ein Karem, which marks the place where he was born.

According to a Greek Orthodox tradition, the saint’s head was held in what is now the crypt after he was executed by Herod Antipas at Machaerus in present-day Jordan. (An early Christian tradition says his body was buried at Sebastiya.)

Centrepiece of pilgrim complex

The traditional view is that the crypt was a church established around 450 by Empress Eudocia, estranged wife of Emperor Theodosius II.

By the 11th century this ancient structure had sunk several metres below street level, and Italian merchants from the maritime republic of Amalfi built the Church of St John the Baptist on top of it. It was the centrepiece of a pilgrim complex including a hospital that treated Crusader knights injured in the 1099 siege of Jerusalem.

Door leading to Church of St John the Baptist among Muristan market shops (Seetheholyland.net)

The presence of the hospital gave the name of Muristan to the area, after the Persian word for hospital or hospice. Some of the injured knights founded what became the Order of Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem (also known as the Knights Hospitaller), the forerunner of the Order of St John.

“As the church of the Hospitallers, St John’s was of great importance during the Crusader period,” said archaeological authority Jerome Murphy-O’Connor.

Benedictine monks and nuns originally administered the church, but by the end of the 15th century the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem had acquired it.

Long and ornate iconostasis

The church stands in a small courtyard, which also contains a monastery of nuns and an ancient well. The facade, with a double bell tower, is a modern addition to the 11th-century building.

Constructed on a trefoil plan without a nave, the church has a green and gold iconostasis that is one of the longest and most ornate in Jerusalem. It is adorned with many icons, some illustrating the life and work of the Baptiser. A golden chandelier hangs in front of the iconostasis.

There is an elegant bishop’s throne and a tiny elevated pulpit at the top of a narrow flight of stairs.

A highly treasured icon on a raised stand depicts the head of John the Baptist on a silver platter. Beside it, within a jewelled silver case, is a piece of skull believed to be a relic of the saint.

Facade and belltower of Church of St John the Baptist (Wikimedia)

Walls covered with murals

Walls and arches are covered with colourful murals and artwork. One of the most striking shows Jesus pulling Adam and Eve from their graves during his descent into Hades, symbolising his victory over both death and Hades.

The four evangelists are portrayed on all four corners of the ceiling, while under each of two arches are representations of the 12 apostles.

In the arched entry area, two murals depict Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist. One shows the archangel Gabriel announcing that his wife Elizabeth would bear a child; the other shows him, struck dumb by Gabriel, writing that his son would be called John.

Related sites:

In Scripture:

The birth of John the Baptist: Luke 1:5-24, 39-66

Herod Antipas executes John the Baptist: Mark 6:14-29; Matthew 14:1-12; Luke 3:18-20

Administered by: Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem

Tel.: +972 2 9943038

Open: Seldom open except for early morning service for the church’s own community.

- Golden dome of Church of St John the Baptist peeps over Muristan roofs (Seetheholyland.net)

- Door leading to Church of St John the Baptist among Muristan market shops (Seetheholyland.net)

- Facade and belltower of Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Icon depicting head of John the Baptist on a platter, beside a jewelled silver case containing a piece of a skull said to be a relic of the saint (© Holy Land Photos)

- Veneration of the saint’s relic during Divine Liturgy on a feast day (© Greek Orthodox Patriarchate)

- Mural showing Jesus pulling Adam and Eve from their graves during his descent into Hades (Seetheholyland.net)

- Glimpse into courtyard of Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Icon of the saint at entrance to courtyard of theChurch of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Mural of the saint’s beheading, in the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Tiny pulpit in the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Bishop’s throne in the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Mural of the Crucifixion in the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Interior of Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Green and gold iconostasis in the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Greek Orthodox nuns entering the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Monastery in courtyard of the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Morning service in Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Monastery cells at Church of St John the Baptist (Alex Ostrovskiy / Wikimedia)

- Facade of Church of St John the Baptist (Alex Ostrovskiy / Wikimedia)

- Golden dome of the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Church of the Redeemer towering over dome of the Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Ancient crypt below Church of St John the Baptist (© TPGPhotos.com)

References:

Bar-Am, Aviva: Beyond the Walls: Churches of Jerusalem (Ahva Press, 1998)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: Keys to Jerusalem (Oxford University Press, 2012)

External link