Jordan

The hilltop fortress of Machaerus, on the eastern side of the Dead Sea and 53 kilometres southwest of Amman, is recorded as the place where John the Baptist was imprisoned and beheaded.

John preached a baptism of repentance at the Jordan River and foretold the coming of Jesus the Messiah, who was his cousin.

He also criticised Herod Antipas, the governor of Galilee and Perea, for unlawfully marrying his half-brother’s wife, Herodias — thereby earning her enmity.

Herod Antipas imprisoned John, but Mark’s Gospel says he protected him, “knowing that he was a righteous and holy man”, and “liked to listen to him” (6:20).

The governor’s birthday banquet for the leaders of Galilee gave Herodias her opportunity to get rid of John. Her daughter, Salome, danced for the gathering and so enthralled Herod that he offered her whatever she wanted — “even half of my kingdom” (6:23).

Salome, who was probably no older than 14 (so her dance might not have been the erotic performance usually imagined), sought her mother’s advice and then asked for John the Baptist’s head.

Herod, “deeply grieved”, gave the order. John was executed and his head brought in “on a platter”. John’s disciples took away his body for burial. (6:26-29)

According to the historian Josephus, John’s execution took place at Machaerus. An early Christian tradition says his body was buried at Sebastiya in Samaria, which Orthodox Christians believe was also the venue for the banquet.

Herod built ‘breathtaking’ palace

Machaerus (the name means “black fortress”) was one of a series of hilltop strongholds established by Herod the Great — the father of Antipas — along the edge of the Jordan Valley and Dead Sea.

Protected on three sides by deep ravines, it afforded seclusion and safety in times of political unrest. Fire signals linked Machaerus to Herod’s other fortresses and to Jerusalem.

On top of the mountain, more than 1100 metres above the Dead Sea, Herod erected a fortress wall with high corner towers. In the centre he built a palace that was “breathtaking in size and beauty”, according to Josephus. Numerous cisterns were dug to collect rainwater.

When Herod the Great died in 4 BC, Machaerus passed to his son Herod Antipas, who ruled Galilee and Perea (an area on the eastern side of the Jordan River) until AD 39.

Jesus appeared before Antipas

Herod Antipas had married Phasaelis, daughter of King Aretas of Nabatea, the kingdom whose capital was Petra. But while visiting Rome in AD 26 he stayed with his half-brother Herod Philip I and fell in love with Philip’s wife Herodias.

When Phasaelis learnt that Antipas intended to divorce her and marry Herodias, she obtained permission to visit Machaerus and from there fled to her father in Nabatea.

Antipas’s rejection of Phasaelis added a personal note to existing disputes with King Aretas over the boundary of Perea and Nabatea. In AD 36 Aretas attacked Antipas and completely destroyed his army.

According to Josephus, some of the Jews saw this devastating defeat as divine retribution for killing John the Baptist.

Some time before the war with Aretas, Jesus was arrested in Jerusalem and brought before Pontius Pilate. When Pilate learnt that Jesus came from Galilee, he sent him to Herod Antipas, who was also in Jerusalem at the time.

Luke’s Gospel says Antipas “had been wanting to see him for a long time” and “was hoping to see him perform some sign”. He questioned Jesus at length, but Jesus gave no answer. Antipas then mocked Jesus and sent him back to Pilate in an elegant robe. (23:8-11)

Romans captured fortress by deception

In AD 39 Herod Antipas was accused of conspiring against the Roman emperor Caligula, who exiled him to Gaul.

At the time of the First Jewish Revolt (AD 66-73), Machaerus was in the hands of Jewish rebels. Roman forces took the fortress only by deception — they captured a young Jewish defender and threatened to crucify him if the rebels did not surrender.

When the rebels agreed to abandon Machaerus, the Romans systematically dismantled the Herodian fortifications.

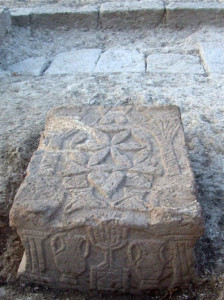

Excavations at the site have uncovered remains of Herod’s palace, including rooms designed around a central courtyard, an elaborate bath and floor mosaics.

Work on partially reconstructing the throne room where Salome is said to have danced was begun by archaeologists in 2020.

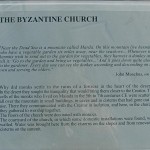

Below the hilltop ruins on the eastern side is the village of Mukawir, where excavations have found evidence of three Byzantine churches built in the 6th century.

In Scripture

Herod Antipas executes John the Baptist: Mark 6:14-29; Matthew 14:1-12; Luke 3:18-20

Jesus appears before Herod Antipas: Luke 23:8-11

- Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1531 (The Yorke Project)

- Columns from Herod’s palace on Machaerus (© Dan Gibson)

- Herod’s stronghold of Machaerus (© Visitjordan)

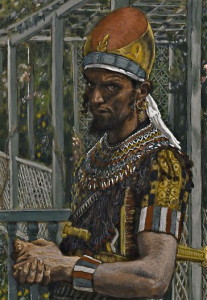

- Herod Antipas, by James Tissot (Brooklyn Museum)

- Ruins of Herod’s palace on Machaerus (© Dan Gibson)

- Machaerus with Dead Sea in background (© Visitjordan)

- Road to Machaerus, with Dead Sea in background (© Dan Gibson)

- Aqueduct footings and water cisterns can be seen on right of road to Machaerus (© Dan Gibson)

- Reconstructed columns of Herod’s palace on Machaerus (© Stanislao Lee / Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

References

Bohstrom, Philippe: “King Herod’s Throne Room Where ‘Salome Danced’ Found in Jordan”, Haaretz, December 14, 2020

Brisco, Thomas: Holman Bible Atlas (Broadman and Holman, 1998)

Cox, Ronald: The Gospel Story (CYM Publications, 1950)

Eber, Shirley, and O’Sullivan, Kevin: Israel and the Occupied Territories: The Rough Guide (Harrap-Columbus, 1989)

Kilgallen, John J.: A New Testament Guide to the Holy Land (Loyola Press, 1998)

Maier, Paul L. (trans.): Josephus: The Essential Writings (Kregel Publications, 1988)

Meyers, Carol L., Craven, Toni, and Kraemer, Ross S. (eds): Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books and New Testament (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2001)

Rainey, Anson F., and Notley, R. Steven: The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Carta, 2006)