Israel/West Bank

Nicopolis (Amwas, Imwas, Emmaus) Map: 31°50’21.48”N, 34°59’22.05”E

Abu Ghosh Map: 31°48’26.6”N, 35°6’28.9”E

El-Qubeibeh (El-Kubeibeh) Map: 31°50’23.76”N, 35°08’12.66”E

Colonia (Kulonieh, Moza, Motza, Ammaous) Map: 31°47’38.11N, 35°10’6.45”E

The village of Emmaus was the setting for one of the most touching of Christ’s post-Resurrection appearances.

Unfortunately for pilgrims drawn by the account in Luke’s Gospel, the identity of Emmaus became lost early in the Christian era. Only in the 21st century are scholars reaching a consensus favouring a location near Moza (or Motza), on the western edge of Jerusalem, where there is no commemorative site to visit.

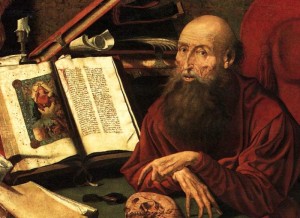

“Supper at Emmaus”, by an anonymous 17th century Italian painter (Wikimedia)

The Emmaus story is well-known: Two disciples downcast by the death of Jesus, and confused by reports that his body is missing, are walking from Jerusalem to Emmaus. They encounter a stranger who listens to their concerns, then gives them a Scripture lesson that makes their “hearts burn within them”.

Finally, as they share the evening meal, he breaks bread and they recognise him. By then the risen Christ has disappeared from their sight, and they immediately hurry back to Jerusalem. (Luke 24:13-35)

Out of several locations for Emmaus proposed over the centuries, expert opinion is focusing on Colonia (or Kulonieh), near the modern Jewish neighbourhood of Moza. Excavations instigated by the New Testament scholar Carsten Peter Thiede at the location from 2001 to 2004 confirmed the existence of an upper-class, 1st-century Jewish village which was called Emmaus.

Disciples may have been father and son

Luke’s Gospel says one of the disciples was named Cleophas. An ancient Christian tradition says he was the brother of St Joseph, the spouse of the Virgin Mary, and that he was later stoned to death outside his own house for declaring that his nephew Jesus was the Messiah foretold by the prophets.

It is believed that the “Mary of Cleophas” who stood by the cross with Jesus’ mother was the wife of the Emmaus disciple.

The same tradition says the other unnamed disciple was the youngest son of Cleophas, called Simeon — who later served for 43 years as head of the Judaeo-Christian Church in Palestine and was martyred at the age of 120.

Several other candidates for the companion of Cleophas have been suggested, including his wife Mary.

Several possible sites suggested

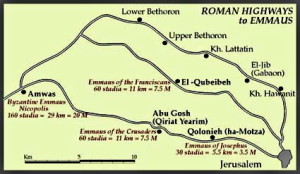

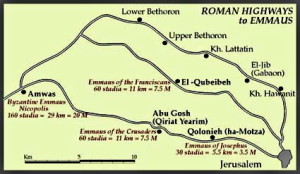

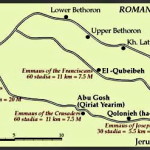

Roads to four possible locations of Emmaus (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

Positively locating the village of Emmaus has been made more difficult by conflicting distances from Jerusalem given in different texts of Luke’s Gospel.

Most texts (including the earliest) give the distance as 60 stadia, but some give it as 160 stadia. A Roman stadion (the plural is stadia) equals 185 metres.

Sixty stadia would be about 11 kilometres (just under 7 miles) and 160 stadia would be 29.5 kilometres (just over 18 miles).

Several possible sites have been proposed over the centuries. The four most seriously considered are:

• Nicopolis (also known as Emmaus, Amwas and Imwas), near Latrun, at the end of the Ayalon Valley, around 160 stadia (30km) from Jerusalem.

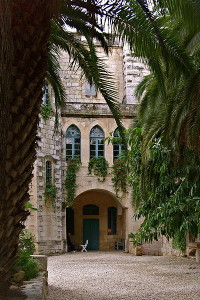

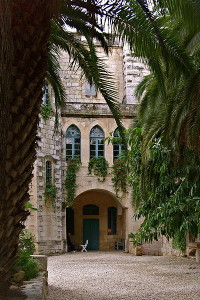

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Cloister of Community of Beatitudes monastery (© Community of the Beatitudes)

Christians in the 4th century considered this the site of Luke’s Emmaus. St Jerome in one of his letters even implied it had a church built in the house of Cleophas. The tradition was so strong that it may have resulted in scribes “correcting” the Gospel text to read 160 rather than 60 stadia. Nevertheless, some of the most ancient manuscripts, such as the Codex Sinaiticus, have 160 stadia.

Around 220, following a delegation led by the prefect of Emmaus, Sextus Iulius Africanus (a prominent Christian), emperor Elagabalus gave Emmaus the status of a city and changed its name to Nicopolis.

The town was wiped out by plague in 639 but, re-established, became the last station of the Crusaders on their way to Jerusalem in 1099. By then the identification with Luke’s Gospel had largely been lost.

In modern times Amwas/Nicopolis was again accepted as Emmaus by 19th-century biblical scholar Edward Robinson. The identification was augmented by revelations received by Blessed Mariam of Jesus Crucified, a nun of the Carmelite monastery of Bethlehem. Advocates of Nicopolis raise the possibility that the disciples arrived back at Jerusalem the day after encountering Christ.

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Ruins of Byzantine church restored by Crusaders (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

The Arab village of Amwas was levelled by Israel following the Six-Day War in 1967. Its ruins are in Ayalon (or Canada) Park, 2km north of Latrun Junction. North of the Cistercian monastery at Latrun are ruins of a large Byzantine church with mosaic floors, within which was built a smaller Crusader church.

Factors against Nicopolis: 1) The distance is much greater than the 60 stadia in most of the earliest Gospel texts. 2) It would have been very difficult for the disciples to walk here from Jerusalem and make the uphill return the same evening before the city gates were shut. 3) The existence of this Emmaus was well-known, so Luke would not have needed to identify it by distance.

Administration: Community of the Beatitudes

Tel.: 972-8-925-69-40

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Benedictine church built by Crusaders (Berthold Werner)

Open: Mon-Sat 8.30-noon, 2.30-5.30pm (5pm Oct-Mar)

• Abu Ghosh, near Kiryat Yearim (or Kiryat el-Enab), just over 60 stadia (11km) west of Jerusalem on the main road to Joppa.

With the Amwas tradition lost, the Crusaders settled on Kiryat el-Enab as Emmaus. They built a church there in 1140 and called the place Castellum Emmaus.

After the Crusaders were defeated 47 years later, Muslims used the church as stables.

This town was previously known as the resting place of the Ark of the Covenant for 20 years between being retrieved from the Philistines and being taken to Jerusalem by King David around 1000 BC.

Early in the 19th century it was renamed Abu Ghosh after a family of brigands who controlled it and exacted tribute from travellers.

The Crusader church, now restored as the Church of the Resurrection, remains one of the finest examples of Crusader architecture. Its tranquil setting adjoins a Benedictine monastery. In the crypt is a spring used by the Roman Tenth Legion when it camped here after capturing Jerusalem in AD 70.

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Faded frescoes in Crusader church (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

On the hill west of the village towers a huge statue of the Madonna and Child surmounting the Church of Our Lady of the Ark of the Covenant. The hill affords an impressive view of the Judean mountains to the east and the coastal plain to the west.

Factors against Abu Ghosh: 1) Kiryat Yearim was not called Emmaus in the 1st century. 2) It was not identified with Luke’s Emmaus until the 12th century.

Administration:

Church of the Resurrection: Benedictines

Tel.: 972-2-5342798

Open: 8.30-11.30am, 2.30-5.30pm (closed on Sundays and Christian feast days, and from Good Friday to Easter Sunday)

Church of Our Lady of the Ark of the Covenant: Sisters of St Joseph of the Apparition

Tel.: 972-2-5342818

Open: 8.30-11.30am, 2.30-5pm (on Sundays phone before visiting).

• El-Qubeibeh (or El-Kubeibeh), on the Roman road to Lydda, just over 60 (11km) stadia northwest of Jerusalem.

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Church of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

With the Crusaders expelled from the Holy Land, Christians in the following centuries were forbidden to use the main highway from the coastal plain to Jerusalem, denying them access to Abu Ghosh.

El-Qubeibeh, which had been part of the agricultural domain of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, was first suggested as St Luke’s Emmaus in 1280. The village was on a Roman road and in 1099 the Crusaders discovered a Roman fortress there, which became known as Castellum Emmaus.

The site was adopted in 1335 by the Franciscans, who began an annual pilgrimage there. Excavation in the 20th century found evidence of occupation in Roman times.

The Franciscans built a church there in 1902, following the lines of the Crusader church. During the Second World War the British used their monastery to inter German and Italian residents of Palestine (including Franciscans).

Roman road at El-Qubeibeh (© vizAviz)

On the façade of the church is a ceramic depiction of Christ and the two disciples. Inside, under glass, are the remains of what is suggested to be the foundations of the house of Cleophas. Near the church a section of Roman road has been excavated.

El-Qubeibeh is the only Emmaus candidate in Palestine, and checkpoints make access more difficult. The elevated site offers a fine outlook over the hill country towards the Mediterranean Sea.

Factors against El-Qubeibeh: 1) The village was not called Emmaus in the 1st century. 2) No Jewish objects have been found there. 3) The village was not identified with Luke’s Gospel until late in the 13th century.

Administration: Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Celebrating feast day of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

Tel.: 050-5200417

Open: 8am-noon, 2-6pm (5pm Oct-Mar)

• Colonia (also called Kulonieh, Emmaus or Ammaous), just over 30 stadia (6km) west of Jerusalem, on the road to Jaffa.

The site now favoured by modern scholars as the most likely Emmaus is just off the highway from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv and adjacent to the modern suburb of Moza.

Ancient Moza (or Mozah) was mentioned as a village of the tribe of Benjamin (Joshua 18:26). In the days of the Temple, according to the Talmud, Moza was the place where Jews collected willow branches for the Feast of Tabernacles.

Emmaus/Colonia: Section of Roman road from Jerusalem to Moza (© BiblePlaces.com)

After the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in AD 70, the emperor Vespasian established a colony of 800 army veterans there. This is recorded by the historian Josephus in The Jewish War. He calls the place “Ammaous”, and overestimates its location as “distant from Jerusalem threescore stadia”. The town subsequently became known as Colonia, after the veterans’ colony.

In modern times, a Palestinian village named Qalunya was destroyed by Jewish forces in 1948. Ruins and a few isolated houses remain. Excavations have revealed evidence of an upper-class, first-century Jewish village.

This Emmaus has no firm Christian tradition linking it to Luke’s Gospel, but it was within easy walking distance of Jerusalem and was known to pilgrims in the 11th and 13th centuries. There is no commemorative site.

Excavations at Moza (Z. Greenhut & A. De Groot excavation, © Israel Antiquities Authority)

Its supporters suggest that Luke’s 60 stadia could refer to the return distance. But there is another possibility. Josephus published The Jewish War in AD 77 or 78. Many scholars believe Luke wrote his Gospel between AD 80 and 85. Could Luke have mistakenly copied the “threescore stadia” from Josephus?

Factors against Colonia: 1) There is no certain link between the Ammaous of Josephus and the Emmaus of Luke. 2) There is no firm Christian tradition. 3) A question mark remains over the distance.

A lesson from elusive Emmaus?

The inability to identify the site of Emmaus with certainty, despite Luke’s richly detailed narrative, may leave devotees as downcast as the two disciples on the road.

They may be consoled by two compensating factors:

“The Walk to Emmaus”, by Gemälde von Robert Zünd (Wikimedia)

• The commemorative “Emmaus” sites at Nicopolis/Amwas, Abu Ghosh and El-Qubeibeh, even if not authentic, are all attractive places to reflect on the message of the Gospel story.

• Perhaps the elusive nature of Emmaus offers its own lesson — that what happened on that day is more important than where it happened, and that encounters with the risen Christ are not confined to one time or place.

In Scripture: The road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13-35)

-

-

“Supper at Emmaus”, by an anonymous 17th century Italian painter (Wikimedia)

-

-

Roads to four possible locations of Emmaus (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Ruins of Byzantine church restored by Crusaders (© Community of the Beatitudes)

-

-

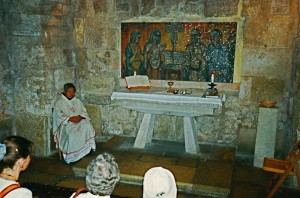

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Eucharist in ruins of church (© Community of the Beatitudes)

-

-

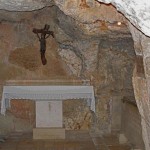

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Altar in ruined church (© Community of the Beatitudes)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Ruins of Byzantine church restored by Crusaders (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Byzantine baptistry (Avishai Teicher / Wikimedia)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Community of the Beatitudes monastery (© Community of the Beatitudes)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Cloister of Community of Beatitudes monastery (© Community of the Beatitudes)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Byzantine mosaic of birds (Wikimedia)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Community of the Beatitudes chapel (© Community of the Beatitudes)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Artwork behind altar in Community of the Beatitudes chapel (© Community of the Beatitudes)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Nearby Cistercian monastery at Latrun (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Emmaus/Nicopolis: Close-up of Latrun monastery (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Entrance to Crusader church (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Benedictine church built by Crusaders (Berthold Werner)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Faded frescoes in Crusader church (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Interior of Crusader church (© Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Fresco in Crusader church (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Fresco in Crusader church (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Ancient steps in Crusader church (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Steps to Roman reservoir under Crusader church (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Crypt of Crusader church (Berthold Werner)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Inscription of Roman Tenth Legion in wall of Crusader church (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Gardens of the Benedictine monastery at Abu Ghosh (Ori / Wikimedia)

-

-

Emmaus/Abu Ghosh: Madonna and Child statue over Church of Our Lady of the Ark of the Covenant (Ori / Wikimedia)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Roman road at El-Qubeibeh (© vizAviz)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Grounds of Franciscan property (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Church of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Celebrating feast day of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Stained-glass window in Church of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Stained-glass window in Church of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Stained-glass window in Church of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Stained-glass window in Church of St Cleophas (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

-

-

Emmaus/Colonia: Sign to Moza on Jerusalem-Jaffa highway (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Emmaus/Colonia: Moza from south-west (© BiblePlaces.com)

-

-

Emmaus/Colonia: Excavations at Moza (Z. Greenhut & A. De Groot excavation, © Israel Antiquities Authority)

-

-

Emmaus/Colonia: Roman road from Jerusalem to Moza (© BiblePlaces.com)

-

-

Emmaus/Colonia: Old synagogue at Moza (Wikimedia)

-

-

“The Walk to Emmaus”, by Gemälde von Robert Zünd (Wikimedia)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Above the altar in the El Qubeibeh church, a wooden triptych represents the Emmaus disciples recognising Jesus in the breaking of bread (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Emmaus/El-Qubeibeh: Foundations of the House of Cleophas displayed on the floor of the El Qubeibeh church (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Brownrigg, Ronald: Come, See the Place: A Pilgrim Guide to the Holy Land (Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

Charlesworth, James H.: The Millennium Guide for Pilgrims to the Holy Land (BIBAL Press, 2000)

De Sandoli, Sabino: Emmaus-el Qubeibe (Franciscan Printing Press, 1980)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Josephus, Flavius: The Jewish War, trans. William Whiston (Kregel, Baker, 1960)

Laney, J. Carl: “The Identification of Emmaus”, from Selective Geographical Problems in the Life of Christ, doctoral dissertation (Dallas Theological Seminary, 1977)

Metzger, Bruce M., and Coogan, Michael D.: The Oxford Companion to the Bible (Oxford University Press, 1993)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Pierri, Rosario: “The Emmaus Enigma” (Holy Land Review, spring 2010)

Thiede, Carsten Peter: The Emmaus Mystery: Discovering Evidence for the Risen Christ (Continuum International, 2006)

Walker, Peter: In the Steps of Jesus (Zondervan, 2006)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

External links

Emmaus (BibleAtlas)

Emmaus (Catholic Encyclopedia)