Israel

Church of the Nativity of St John the Baptist

Christian tradition places the birth of John the Baptist — who announced the coming of Jesus Christ, his cousin — in the picturesque village of Ein Karem 7.5km south-west of Jerusalem.

Luke’s Gospel tells of the circumstances of John’s birth (1:5-24, 39-66).

The angel Gabriel appeared to the elderly priest Zechariah while he was serving in the Temple and told him that his wife Elizabeth was to bear a son. Zechariah was sceptical, so he was struck dumb and remained so until the baby John was born.

In the meantime, Gabriel appeared to the teenage Virgin Mary in Nazareth, telling her that she was to become the mother of Jesus. As proof, he revealed that Mary’s elderly cousin Elizabeth was already six months’ pregnant.

Mary then “went with haste to a Judean town in the hill country” — a distance of around 120km — “where she entered the house of Zechariah and greeted Elizabeth. When Elizabeth heard Mary’s greeting, the child leaped in her womb.” (Luke 1:39-41)

Two sites for two houses

The two main sites in the “Judean town” of Ein Karem are linked to the understanding that Zechariah and Elizabeth had two houses in Ein Karem (also known as Ain Karim, Ain Karem, ’Ayn Karim and En Kerem).

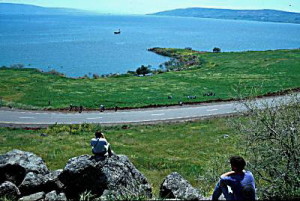

Their usual residence was in the valley. But a cooler summer house, high on a hillside, allowed them to escape the heat and humidity.

The summer house is believed to be where the pregnant Elizabeth “remained in seclusion for five months” (Luke 1:24) and where Mary visited her.

The house in the valley is where John the Baptist was born. Here, also, old Zechariah finally regained his power of speech after his son was born, when he obediently wrote on a writing tablet that the baby’s name was to be John.

Ein Karem is still a tranquil place of trees and vineyards, but the municipality of Jerusalem has spread to incorporate the former Arab village. It is now a town of Jewish artisans and craftspeople, but Christian churches and convents abound.

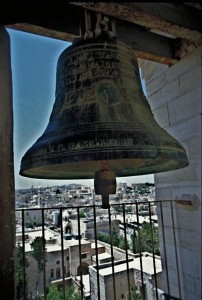

Church of the Nativity of St John the Baptist

There are two major churches of St John the Baptist in the town. Best-known is the Catholic Church of the Nativity of St John, identifiable by its tall tower topped by a round spire. It is also called “St John in the mountains”, a reference to the “hill country” of the Scripture.

The church combines remnants of many periods. An early church on this site was used by Muslim villagers for their livestock before the Franciscans recovered it in the 17th century. The Franciscans built the present church with the help of the Spanish monarchy.

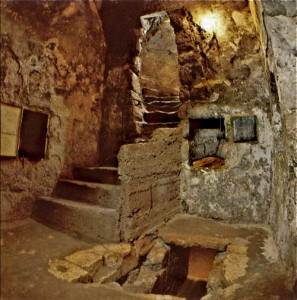

The high altar is dedicated to St John. To the right is Elizabeth’s altar. To the left are steps leading down to a natural grotto — identified as John’s birthplace and believed to be part of his parents’ home.

A chapel beneath the porch contains two tombs. An inscription in a mosaic panel reads, in Greek, “Hail martyrs of God”. Whom it refers to is unknown.

The other church, built in 1894, is Eastern Orthodox.

Church of the Visitation

The Virgin Mary’s visit to Elizabeth — depicted in mosaic on the façade — is commemorated in a two-tiered church, on a slope of the hill south of Ein Karem.

Completed in 1955 to a design by Antonio Barluzzi, the artistically decorated Church of the Visitation is considered one of the most beautiful of all the Gospel sites in the Holy Land.

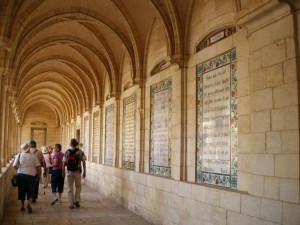

This is believed to be the site of Zechariah and Elizabeth’s summer house, where Mary came to visit her cousin. On the wall opposite the church, ceramic plaques reproduce Mary’s canticle of praise, the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55) in some 50 languages.

In the lower chapel, a vaulted passage leads to an old well. An ancient tradition asserts that a spring joyfully burst out of the rock here when Mary greeted Elizabeth.

A huge stone set in a niche is known as the Stone of Hiding. According to an ancient tradition, the stone opened to provide a hiding place for the baby John during Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents — an event depicted in a painting on the wall.

Mary’s Spring and the Desert of St John

In a valley on the south of the village is a fresh-water spring known as Mary’s Spring or the Fountain of the Virgin. Tradition has it that Mary quenched her thirst from this spring before ascending the hill to meet Elizabeth.

The water has become contaminated and is no longer safe to drink.

The spring gives the village its name — from the Arabic “ein” (spring) and kerem (vineyard or olive grove). Built over the spring is a small abandoned mosque, another reminder that this was once an Arab village.

South-west of Ein Karem, off Route 386, a Greek Melkite monastery and a Franciscan convent mark the Desert of St John, a site where John the Baptist is believed to have lived in seclusion.

In Scripture:

The birth of John the Baptist: Luke 1:5-24, 39-66

Mary visits Elizabeth: Luke 1:39-45

The Magnificat: Luke 1:46-55

Administered by: Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land

Tel.: Visitation Church 972-2-6417291; St John’s Church 972-2-6323000

Open: St John’s Church, 8am-noon, 2.30-5.45pm (4.45pm Oct-Mar); Visitation Church, 8-11.45am, 2.30-6pm (5pm Oct-Mar)

- Icon of John the Baptist, in Church of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, Ein Karem (Seetheholyland.net)

- John the Baptist’s death, in Church of John the Baptist (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Mural of Mary meeting Elizabeth, in Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

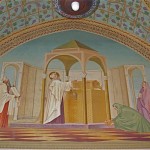

- Mural of Zechariah burning incense in the Temple, in Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Church garden at Ein Karem (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

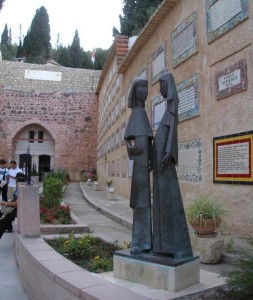

- Statue of St Zechariah in grounds of Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Steep steps to the Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Rock said to have sheltered John during the Massacre of the Innocents, in Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Wall plaque in Church of the Visitation (© Deror Avi)

- Mosaic in Church of the Visitation (© Deror Avi)

- Mary meets Elizabeth, at the Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Magnificat in Arabic at Church of the Visitation (© Deror Avi)

- Upper church in Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Mosaic in Church of the Visitation (© Deror Avi)

- Church of the Visitation, Ein Karem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Inside Church of John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- John baptising Jesus, in Church of John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Statue of John the Baptist in Church of John the Baptist (© Custodia Terrae Sanctae)

- Children playing at Mary’s Spring, Ein Karem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Gateway to Church of John the Baptist, Ein Karem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Terraced hill at Ein Karem (Seetheholyland.net)

- Cloisters at Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Plaques of the Magnificat at Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Grotto of the Benedictus in Church of St John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

- Church of St John the Baptist in the centre of Ein Karem (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Mural of Elizabeth escaping with John from the Massacre of the Innocents, in Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Altar in crypt, Church of the Visitation (© Deror Avi)

- Monastery of St John in the Desert (Wikimedia)

- Mosaic of Mary on her way to Elizabeth, on Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- Plaque marking traditional place of John the Baptist’s birth, in Church of John the Baptist (© Deror Avi)

- A striking mural of the Virgin Mary by French artist A. D’Acchille, in the Church of the Visitation (Seetheholyland.net)

- A pilgrim knees in the Grotto of the Benedictus in the Church of St John the Baptist (Kristina Fuiava / Seetheholyland.net)

References

Brownrigg, Ronald: Come, See the Place: A Pilgrim Guide to the Holy Land (Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Inman, Nick, and McDonald, Ferdie (eds): Jerusalem & the Holy Land (Eyewitness Travel Guide, Dorling Kindersley, 2007)

Kloetzli, Godfrey: “Ain Karim”, Holy Land, winter 2003

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

External links