Israel

View from Masada to the Dead Sea (Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

The rocktop fortress of Masada overlooking the Dead Sea has been invested with a quasi-religious significance as a symbol of resistance for the people of Israel.

Once a palatial refuge for Herod the Great, this massive plateau on the eastern edge of the Judean Desert is better known as the location of a Roman siege against Jewish rebels in AD 74.

The story of 960 defenders choosing self-inflicted death rather than surrender has achieved legendary status for the Jewish people, though scholars have questioned its credibility.

Masada’s symbolic status was boosted by a poem by Yitzchak Lamdan, published in 1927, and by extensive excavations by soldier-archaeologist Yigael Yadin.

Masada’s summit may be reached by a tortuous “snake path” (which takes a fit person 45 minutes), by a path up the Roman siege ramp (15 minutes) or by a modern cable car.

The view across the Dead Sea 450 metres below is spectacular. After Jerusalem, Masada is Israel’s most popular tourist attraction.

Herod lived in luxury

Bathhouse with under-floor heating (Seetheholyland.net)

Masada’s flat-topped shape has been aptly described by Jerome Murphy-O’Connor as “curiously like an aircraft-carrier moored to the western cliffs of the Dead Sea”.

The north-facing prow of this warship consists of the ruins of Herod’s luxurious residential palace. Elaborately designed and decorated, it cascaded in three tiers down the cliff face, each tier connected by a rock-cut staircase.

On the western side of the warship’s 550m by 275m deck are the remains of Herod’s ceremonial palace and administrative centre. The largest building on Masada, it covered nearly half a hectare.

Herod planned Masada as a palace stronghold and desert foxhole, and fortified it with walls, gates and towers. He wanted a place of refuge in case the Jews should rebel against him, or the Egyptian pharaoh Cleopatra (who coveted Judea) should try to have him killed.

Herod’s creature comforts include bathhouses and a swimming pool. The most elaborate bathhouse had a hot room with the floor suspended on low pillars. Hot air from a furnace was circulated under the floor and through clay pipes in the walls.

To supply water in this arid setting, a sophisticated system channelled winter rainfall from nearby wadis into huge cisterns quarried low into the northwest of the mountain. Water was then carried by men and beasts of burden up winding paths to reservoirs on the summit. The lower cisterns alone are estimated to have a capacity of 38,000 cubic metres.

Romans besieged the fortress

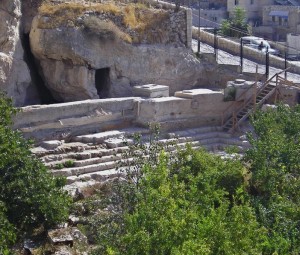

Seige ramp at Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

In AD 66, at the beginning of the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome, a group of Jewish extremists called Sicarii overran the Roman garrison stationed on Masada. By then, Herod had been dead for 70 years.

According to the historian Josephus, the Sicarii were unlikely heroes who attacked local villages. In a night raid for food on the Jewish settlement of En-Gedi, 17km away, he says the Sicarii killed more than 700 Jewish settlers, including women and children, during Passover.

The Roman governor Lucius Flavius Silva waited until Jerusalem had fallen before taking the Tenth Legion to Masada in 72-73. Laying siege to the fortress, he established eight fortified camps linked by a ditch and wall around Masada, then built a ramp on top of a natural bedrock spur to reach the summit.

Up the ramp the Romans rolled an iron-sheathed siege tower, with rapid-firing catapults and a huge battering ram to breach the fortress wall.

According to Josephus, when defeat was inevitable the leader of the Sicarii, Eleazar ben Ya’ir, gave two impassioned speeches persuading his companions to cast lots to kill each other rather than be taken prisoner.

He argued “it is still an eligible thing to die after a glorious manner, together with our dearest friends . . . let us bestow that glorious benefit upon one another mutually, and preserve ourselves in freedom, as an excellent funeral monument for us”.

When the Romans stormed the summit, they found the bodies of 960 occupants. The only survivors were two women and five children who had hidden in a cistern.

Josephus’ account is questioned

The only account of the fall of Masada and the mass suicide of its occupants comes from Josephus. Surprisingly, the Jewish rabbis who wrote the Talmud did not record the event.

A former Jewish rebel who joined the Romans after he was captured, Josephus lived through the Great Jewish Revolt and knew Silva personally. Like other historians of antiquity, however, he was known for his literary embellishments, and scholars have questioned the credibility of his dramatic account.

Would there have been time for Eleazar’s speeches, the drawing of lots and the organized killings as Masada fell? Would the survivors have been able to repeat the speeches verbatim to the Romans?

More pertinently, modern historians point to parallels between Eleazar’s second oration and a speech Josephus himself gave in similar circumstances when the fortified village of Jotapata, in northern Galilee, fell to the Romans after a siege and bloody battle in AD 67.

Josephus, who commanded the Jewish rebels in Galilee in that battle, tells of hiding in a cave with other survivors who drew lots to kill each other rather than surrender. One of the last two men standing — “should one say by fortune or by the providence of God?” — was the wily Josephus, who persuaded his companion to join him in surrendering.

Rather than accept the rhetoric of Josephus, modern historians favour a more chaotic climax at Masada, with some Sicarii fighting to the death, some taking their own lives and others trying to hide.

Furthermore, a research report in 2016 concluded that the ramp was never completed and therefore could not have been used to capture the fortress.

Restored buildings can be seen

Many of the buildings on Masada’s summit have been restored, including Herod’s bathhouses (a black line on the walls indicates where restoration began). Some have mosaic floors.

Remains of a synagogue used by the Sicarii and a church built by Byzantine monks in the 5th century have also been excavated. The monks lived in cells dispersed round the summit.

Silva’s siege works and ramp, including remains of the Roman wall and camps, can still be seen.

The skeletons of 28 people excavated in the 1960s — whether Sicarii or Roman soldiers is not proven — were given a state funeral at Masada with full military honours in 1969.

In the early decades of the Jewish state, recruits to Israel’s armed forces — in which service is compulsory for most citizens, male or female — climbed the snake path for a torchlight swearing-in ceremony ending with the declaration: “Masada shall not fall again!”

The ceremony was abandoned in 1986, according to Rabbi Lawrence Hoffman, because “Its underlying message of heroes who commit suicide no longer captured the imagination of a Jewish state which emphasised life, not death, and victory rather than defeat”.

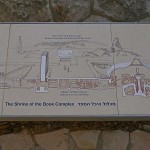

Administered by: Israel National Parks Authority

Tel.: 08-658-4207/8

Open:

April–September 8 A.M.–5 P.M. October–March 8 A.M– 4 P.M. Fridays and holiday eves, site closes one hour earlier than above.

Cable-car hours: Sat.–Thurs.: 8 A.M.–4 P.M.; Friday and holiday eves 8 A.M.–2 P.M.; Yom Kippur eve 8 A.M.–noon.

-

-

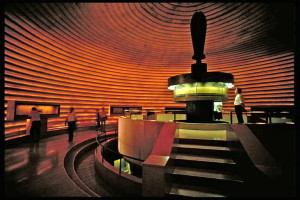

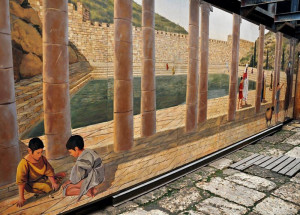

Israel Museum impression of what Herod’s residential palace would have looked like (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Snake path and cablecar ropes (Charles Meeks)

-

-

Seige ammunition at Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

View from Masada to the Dead Sea (Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Remains of middle terrace of Herod’s palace (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Mosaic repairs in Byzantine church on Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Lowest level of Herod’s three-tiered palace (Charles Meeks)

-

-

Model showing Herod’s three-tiered palace on Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Byzantine church on Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Remains of mural in bath house (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Mosaic at Masada (© Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Seige ramp at Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Snake path to top of Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Line marking where reconstruction began (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Looking from Masada towards the Dead Sea (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

-

-

Inside Byzantine church on Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Mosaic floor at Masada (© Tom Callinan / Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Reconstructed storerooms on Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Mosaic floor at Masada (Picturesfree.org)

-

-

Bathhouse with under-floor heating (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Notice at Byzantine church on Masada (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Brownrigg, Ronald: Come, See the Place: A Pilgrim Guide to the Holy Land (Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

Charlesworth, James H.: The Millennium Guide for Pilgrims to the Holy Land (BIBAL Press, 2000)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Goldfus, H., et al.: “The significance of geomorphological and soil formation research for understanding the unfinished Roman ramp at Masada”, Catena, 2016

Hoffman, Lawrence A.: Israel: A Spiritual Travel Guide (Jewish Lights Publishing, 1998)

McCormick, James R.: Jerusalem and the Holy Land (Rhodes & Eaton, 1997)

Maier, Paul L. (trans.): Josephus: The Essential Writings (Kregel Publications, 1988)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Rainey, Anson F., and Notley, R. Steven: The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Carta, 2006)

Walker, Peter: In the Steps of Jesus (Zondervan, 2006)

Wareham, Norman, and Gill, Jill: Every Pilgrim’s Guide to the Holy Land (Canterbury Press, 1996)

External links

The Wars of the Jews, by Josephus (Christian Classics Ethereal Library; chapters 8 and 9 describe the siege of Masada)

Masada (Bible Pictures)