Israel

Just before Christmas in 2022 the discovery of “the tomb of holy Salome, the midwife of Mary”, near Tel Lachish in central Israel, was announced.

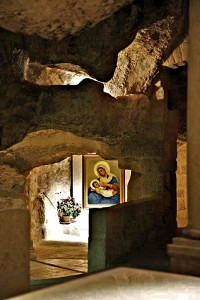

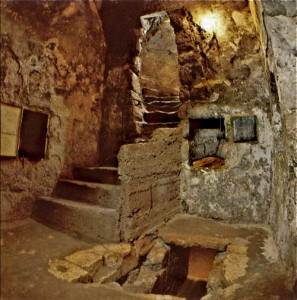

Interior of the family tomb in Salome’s Cave. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

Yes, there was a tomb venerated in Byzantine times as belonging to the Salome mentioned in the New Testament. But it was not a recent discovery, having been earlier identified in the 1980s. And even if it was the tomb of Salome, she was not the midwife at the birth of Jesus.

The Gospels indicate that Salome, the mother of the apostles James and John, was a follower of Jesus who accompanied him from Galilee and helped provide for him. She was present at the Crucifixion and went to his tomb on Easter Sunday to anoint his body. A common interpretation identifies her as the sister of Jesus’ mother, thus making her Jesus’ aunt.

She is also referred to as “the mother of the sons of Zebedee” who prompted discord among the disciples by asking Jesus to have one of her sons sit on his right side and the other on his left side in his kingdom.

This Salome should not be confused with the dancing step-daughter of Herod Antipas, who procured the death of John the Baptist (Mark 6:14-29). She is not named in the Gospels, though the Jewish historian Josephus identifies her as Salome.

She doubted virgin birth

Salome’s name appears frequently in apocryphal writings — works of uncertain authenticity and not deemed part of the canonical Scriptures. It is from one of these, the Protoevangelium of James (also known as the Infancy Gospel of James), that she became known as Mary’s midwife.

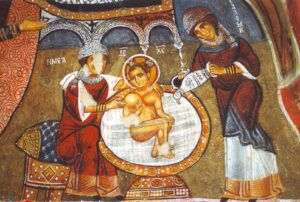

Salome (right) and the midwife bathing the infant Jesus in a 12th-century fresco (Open Air Museum, Goreme, Cappadocia)

However, this second-century narrative about the earlier stages of the life of Mary and about Jesus’ birth does not name Salome as the midwife.

It describes Joseph leaving Mary in a cave outside Bethlehem, with his two sons guarding the entrance, while he went to find a Hebrew midwife. They returned to find a brilliant light filling the cave and as it dimmed they glimpsed a newborn baby.

As the midwife left the cave she met Salome and exclaimed that a virgin had given birth. But Salome was not convinced, declaring “As the Lord my God lives, unless I thrust in my finger, and search the parts, I will not believe that a virgin has brought forth.”

When Salome’s test confirmed the midwife’s claim, her hand withered up in pain. But an angel appeared, telling Salome she would be healed if she touched the baby. Salome was healed and worshipped Jesus.

Jewish imagery and Christian chapel

The burial cave associated with Salome was discovered about 35 kilometres south-west of Jerusalem by antiquity looters in 1982 and excavated by the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1984. Despite ample proof of being a Christian pilgrimage site from the Byzantine era, it was never opened to the public.

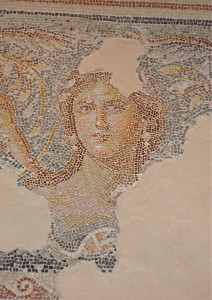

The elaborate tiled forecourt of Salome’s Cave (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

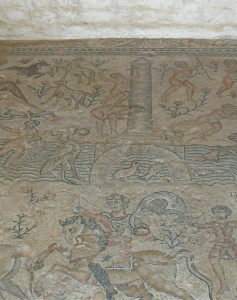

In 2022 archaeologists excavated an elaborate tiled forecourt at the entrance to the cave, filled with intricate stone carvings, soaring arches, a mosaic floor, and the remains of a small marketplace with hundreds of oil lamps, which pilgrims may have rented to light their way into the cave.

The ornate cave, one of the most impressive discovered in Israel, presumably belonged to Salome’s wealthy Jewish family. Replete with Jewish imagery, it features a later Christian chapel with crosses carved into the walls and dozens of inscriptions from the Byzantine and Muslim periods in three languages — Greek, Syriac and Arabic.

The ancient graffiti includes the words “Salome”, “Jesus”, the names of pilgrims, and crosses etched into the wall. The most notable inscription, in Greek, reads “Zacharia Ben Kerelis, dedicated to the Holy Salome”. Archaeologists believe that Zacharia Ben Kerelis was a wealthy Jewish patron who funded the construction of parts of the burial cave and courtyard.

On Judean Kings Trail

The excavation by the Israeli Antiquities Authority was undertaken to open the cave to the public as part of the Judean Kings Trail, a 100km trail from Beersheba to Beit Guvrin featuring dozens of archaeological sites.

The area also has significance for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Among its members is a belief that the nearby site of Beit Lehi could have been the home of Lehi, a Hebrew prophet who in the Book of Mormon led his family and followers from Jerusalem to a promised land somewhere in the Americas. A Mormon group, the Beit Lehi Foundation, has also worked at Salome’s cave.

In Scripture

Matthew 20:20: Salome asks Jesus for a favour

Matthew 27:56: Salome at the Crucifixion

Mark 15:40-41: Salome at the Crucifixion

Mark 16:1: Salome preparing to anoint Jesus’ body

- The entrance to Salome’s Cave in Lachish Forest. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- The elaborate family tomb in Salome’s Cave. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Interior of the family tomb in Salome’s Cave. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Inscriptions left by pilgrims on the walls at Salome’s Cave. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Oil lamps uncovered during the archaeological excavation at Salome’s Cave. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Devotional pictures in the family tomb at Salome’s Cave. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- The elaborate tiled forecourt of Salome’s Cave (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Clay lamps from the eighth to ninth centuries discovered during excavations (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Inside the elaborate family tomb in Salome’s Cave. (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Excavations in the forecourt of Salome’s Cave (©️Emil Eljam / Israel Antiquities Authority)

- Salome (right) and the midwife bathing the infant Jesus in a 12th-century fresco (Open Air Museum, Goreme, Cappadocia)

- Salome (left) depicted as Mary’s midwife in a 14th-century fresco by Giotto di Bondone (Arena Chapel, Padua)

References

Bowker, John: The Complete Bible Handbook (Dorling Kindersley, 1998)

Davies, Stevan: The Infancy Gospels of Jesus: Apocryphal Tales from the Childhoods of Mary and Jesus (SkyLight Paths Publishing, 2009)

Schuster, Ruth: “Evidence of Christian Pilgrimages Found at ‘Tomb of Jesus’ Midwife’ in Israel”, Haaretz, December 20, 2022

Siegel-Itzkovich, Judy: “Elaborate burial cave found at site in southern Israel venerated for centuries”, Jerusalem Post, December 20, 2022

External links

Gospel of James (Wikipedia)

Protoevangelion of James (Orthodox Wiki)

Protoevangelium of James (New Advent)

Salome Tomb (Beit Lehi Foundation)