West Bank

Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

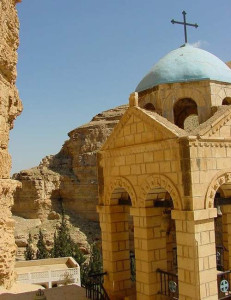

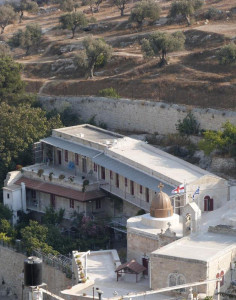

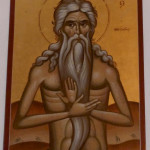

The Monastery of St Gerasimus, one of the earliest of the 70-plus monasteries in the Judaean desert, is named in honour of a pioneering monk who is usually depicted with a pet lion.

A verdant and welcoming oasis in the arid lower Jordan Valley, it is on the east side of highway 90 just north of the Beit-Ha’aravah junction, and about 7 kilometres southeast of Jericho.

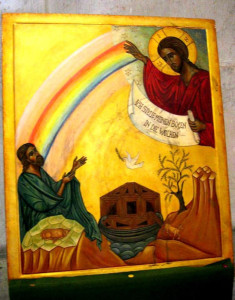

Across the Jordan River is the place of Jesus’ baptism, Bethany Beyond the Jordan, but the two-storey monastery commemorates an earlier event in Jesus’ life.

According to an old tradition, the monastery was built where Mary, Joseph and the infant Jesus took shelter in a cave while fleeing from Herod the Great.

This event is commemorated in the ground-floor crypt beneath the monastery church. An icon illustrates the Flight of the Holy Family into Egypt and a large painting depicts a contented Jesus being nursed at the breast by his mother Mary.

Fresco of St Gerasimus with his lion (Bukvoed)

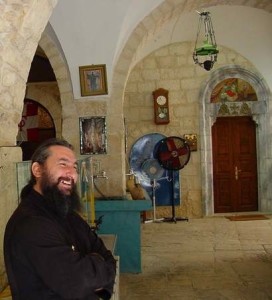

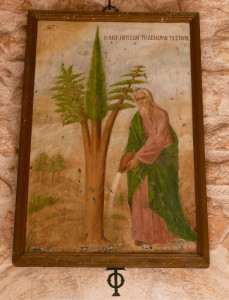

The upper-floor church contains many holy icons and frescoes, including paintings of Gerasimus and his lion. Cabinets in the crypt store the bones of monks killed during the Persian invasion of 614.

Hospitable place for pilgrims

A place of hospitality and refreshment for pilgrims, with fruit trees, flowers and birdsong, the gold-domed monastery offers a contrast to the hot and barren environment of the Judaean wilderness.

Founded in the fifth century, it was originally dedicated to Our Lady of Kalamon (Greek for reeds), but was later renamed in honour of Gerasimus, who founded a nearby monastery that had been abandoned.

It was destroyed in 614, rebuilt by the Crusaders, abandoned after the Crusader period, restored in the 12th century, rebuilt in 1588, destroyed around 1734 and re-established in 1885.

In Arabic it is known as Deir Hajla, meaning the monastery of the partridge, a bird common to the area.

Cloister in Monastery of St Gerasimus (© Deror Avi)

The monastery functioned in the form of a laura — with a cluster of hermits’ caves located around a community and worship centre. The hermits spent weekdays alone in their caves, occupied in prayer and making ropes and baskets. They went to the centre for Saturdays and Sundays, taking their handiwork and partaking in Divine Liturgy and communal activities.

The monastic rule was strict. During the week the hermit monks survived on dry bread, dates and water. At the weekends they ate cooked food and drank wine. Their only personal belongings were a rush mat and a drinking bowl.

Hermits’ caves can still be seen in the steep cliffs a kilometre east of the monastery and in the adjacent mountains.

Gerasimus redeveloped monastic life

Like many who founded Judaean monasteries, Gerasimus (also spelt Gerassimos or Gerasimos) came from outside the Holy Land — from a wealthy family in Lycia, in present-day Turkey.

Already a monk when he came to Palestine, he followed the monastic leader Euthymius into the desert and became renowned for his piety and asceticism.

Because of the similarity of names, Gerasimus is sometimes confused with St Jerome, the Bible translator who lived in Bethlehem.

Gerasimus is credited with a new development in monastic life. Previously desert monks lived either in caves or in monasteries. He was the first to combine the solitude of a wilderness hermit with the communal aspect of a monastery by bringing hermits together on Saturdays and Sundays for worship and fellowship.

Upper part of iconostasis in monastery church (© Deror Avi)

He is believed to have attended the crucial Council of Chalcedon in 451, which caused a major rift in the Eastern Orthodox world.

Called to settle differences of opinion on the nature of Christ, the council declared that he has two natures in one Person as truly God and truly man. Gerasimus briefly opposed this declaration, then accepted it.

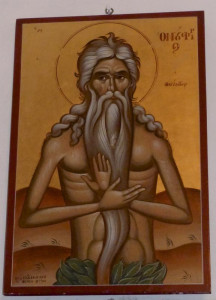

The lion depicted in icons of Gerasimus comes from a story that he found the animal wandering in the desert, suffering from a thorn embedded in a paw. The saint gently removed the thorn and tended to the wound.

The lion thereafter devoted himself to Gerasimus, serving him and the monastery and retrieving the monastery’s donkey when it was stolen by thieves.

The story has it that when Gerasimus died in 475 the lion lay on his grave and died of grief.

Administered by: Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem

Tel.: +972 2 9943038

Open: 8am-6pm daily

- Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Fresco of St Gerasimus with his lion (Bukvoed)

- High defensive wall surrounding the monastery (Bukvoed)

- Ground-floor entrance to the monastery (Bukvoed)

- Mosaic of St Gerasimus’s lion in the monastery (Deror Avi)

- Bell tower of Monastery of St Gerasimus (© Deror Avi)

- Cloister in Monastery of St Gerasimus (© Deror Avi)

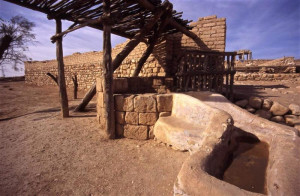

- Well in courtyard of Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Frescoes and icons in nave of monastery church (Bukvoed)

- View across nave of monastery church (Bukvoed)

- Fresco of the death of Mary in monastery church (Bukvoed)

- Iconostasis in monastery church (Bukvoed)

- Upper part of iconostasis in monastery church (© Deror Avi)

- Saints depicted in frescoes in monastery church (Bukvoed)

- God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit in dome of monastery church (© Deror Avi)

- Mary suckling Jesus, in Monastery of St Gerasimus (© Deror Avi)

- Icons in the crypt of the monastery (Bukvoed)

- Cloister in Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Greek Orthodox pilgrimage centre at Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Dovecote on wall of Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Skulls of martyred monks displayed in monastery (Bukvoed)

- Remains of victims massacre and earthquake in Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Skulls of martyred monks in Monastery of St Gerasimus (© Deror Avi)

- Graves at Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Mosaic under construction at Monastery of St Gerasimus (Bukvoed)

- Containers of tesserae to be used in mosaic at Monastery of St Gerasimus (© Deror Avi)

References

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Irving, Sarah: Palestine (Bradt Travel Guides, 2011)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Prag, Kay: Israel & the Palestinian Territories: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 2002)

Rossing, Daniel: Between Heaven and Earth: Churches and Monasteries of the Holy Land (Penn Publishing, 2012)