Israel

Beit She’an offers the most extensive archaeological site in Israel, with some of the best-preserved ruins in the Middle East, but its memory will forever be linked to one of the most ghoulish events in the Bible.

On nearby Mount Gilboa in 1004 BC, the army of King Saul, Israel’s first king, was defeated by the Philistines and Saul’s three sons were killed. To avoid capture, the wounded Saul fell on his sword.

The triumphant Philistines took the bodies of Saul and his sons and fastened them to the wall of Beit She’an. They put Saul’s armour in their temple.

David, who was to succeed Saul as king, composed a memorable lament over the tragedy, with the recurring line “How the mighty have fallen . . . ” (2 Samuel 1:17 – 27).

Beit She’an is about 13 kilometres south of the Sea of Galilee. Its location at the strategic junction of the Jezreel and Jordan valleys made it a coveted prize for conquerors.

Apart from the Philistines, its rulers included Egyptians, Israelites (though the Canaanite inhabitants initially rebuffed them), Greeks and Romans.

In the Roman period — under the name of Scythopolis — it was the leading city of the Decapolis and the only one of these 10 semi-autonomous cities west of the Jordan River.

From the 4th century until it was destroyed by an earthquake in 749, the formerly pagan city was a flourishing Christian centre, with a bishop and several churches.

City’s population grew to 40,000

Beit She’an began on the flat-topped hill that stands behind the ruins of the Roman-Byzantine city. This ancient tell, 80 metres high, contains 18 levels of occupation down to the first settlers around 4000 BC.

In Roman times the inhabitants moved to the flat area at the foot of the hill. Here the city expanded to around 150 hectares in area, with wide colonnaded streets leading to elegant shops with marble facades and mosaic floors.

The population of Scythopolis grew to 40,000 and the linen it produced made it one of the leading textile centres of the Roman empire. Centuries later it became a centre for processing cane sugar.

Excavations have revealed:

• A three-tiered theatre for dramatic performances, seating 7000 people.

• An amphitheatre holding 6000, where gladiatorial contests entertained soldiers of the Sixth Legion which was based here.

• A huge bath and gym complex with swimming pools and halls heated by hot air from furnaces. Its public toilets had channels underneath with running water.

• A Roman basilica that served as a courthouse and administrative centre.

• A nymphaeum, an elaborate monumental building with a decorative fountain.

• A mosaic of Tyche, the Roman goddess of good fortune, wearing the walled city of Scythopolis as a crown and holding the horn of plenty in her hand.

Circular church replaced temples

On the summit of the tell, a steep climb obtains a sweeping panorama of the ruins below, the Jordan and Harod valleys and Mount Gilboa.

Here a great circular church, with a cloister around an open court, replaced the earlier Canaanite and Philistine temples during the Byzantine era.

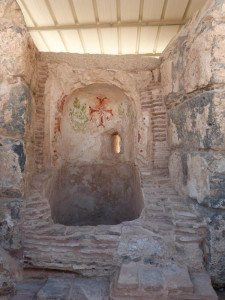

Among the other churches in the lower city, one was dedicated to Procopius, a local martyr. Its location is unknown, but remains of other church buildings have been found and a striking red cross can be seen on the plaster wall of a niche in a bathhouse, probably used as a baptistry.

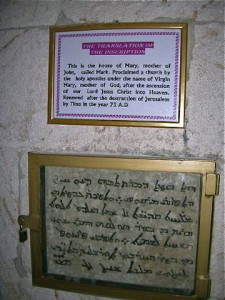

The modern town of Beit She’an has encroached on some of the ancient ruins. One of these is the Monastery of the Lady Mary, founded in 567 and named after a donor, perhaps the wife of a Byzantine official.

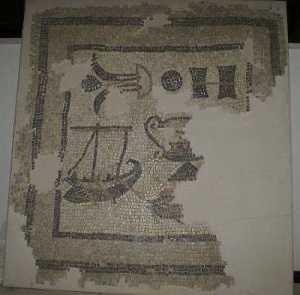

This complex — not usually open to the public — contains a series of rooms with beautiful mosaic floors. The mosaic in the central hall of the chapel depicts animals such as lions, camels, boars and ostriches around a zodiac illustrating the months of the year.

Interestingly, the remains of Jewish and Samaritan synagogues have been found along with churches from the time when Scythopolis was a Christian city. And after a Muslim army conquered the city in 634 and renamed the city Baysan, Christians and Muslims lived together until the disastrous earthquake of 749.

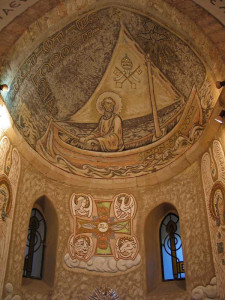

Cross on wall identifies a probable baptistry at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

In Scripture

Canaanites of Beit She’an resist Manasseh: Judges 1:27

Philistines fasten Saul’s body to Beit She’an wall: 1 Samuel 31:10

Administered by: Israel National Parks Authority

Tel.: +972-4-658-7189

Open: Apr-Sept 8am-5pm (except Friday 8am-4pm); Oct-Mar 8am-4pm (except Saturday 8am-5pm). Last entry to site one hour before closing time.

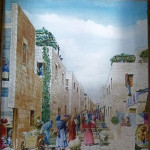

- Silhouettes of local residents on main street of Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Wooden-wheeled invention for transporting heavy stone blocks at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Cross on wall identifies a probable baptistry at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Carved capital from a column at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Date palm at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Caldarium (steam room) in the public bathhouse at Beit She’an (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Flower engraved in limestone beam at Beit She’an (James Emery)

- Remains of Roman theatre at Beit She’an, which seated 7000 people (Seetheholyland.net)

- Main street and tell at Beit She’an (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

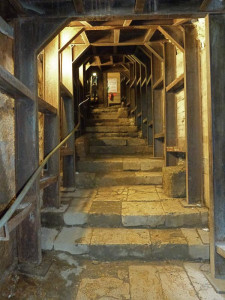

- Steep track to top of tell at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Reconstructed columns at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Bronze Age Egyptian bust at Beit She’an (James Emery)

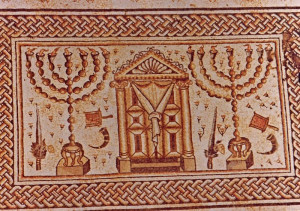

- Cross motif from the Monastery of the Lady Mary, Beit She’an (Yair Talmor)

- General view of ruins at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Stage in theatre at Beit She’an (Steve Peterson)

- Ruins of Beit She’an from the tell, with modern town in background (Steve Peterson)

- Beit She’an remains, with site of odeon (a building for musical performances) at left (Seetheholyland.net)

- Columns toppled by the AD 749 earthquake at Beit She’an (Kasper Nowak)

- Amphitheatre at Beit She’an (James Emery)

- Restored corner of Roman theatre at Beit She’an (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Archway and columns at Beit She’an (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Reconstructed colonnade at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Colonnaded street leading to tell at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- Very public toilets at Beit She’an (Seetheholyland.net)

- View from stage of theatre at Beit She’an (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Model of Roman city of Beit She’an (James Emery)

- Beit She’an ruins viewed from Roman theatre (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Beit She’an in about 1925, before the Roman-Byzantine city in front of the mound was excavated. (American Colony/Eric Matson collection)

References

Blaiklock, E. M.: Eight Days in Israel (Ark Publishing, 1980)

Bourbon, Fabio, and Lavagno, Enrico: The Holy Land Archaeological Guide to Israel, Sinai and Jordan (White Star, 2009)

Charlesworth, James H.: The Millennium Guide for Pilgrims to the Holy Land (BIBAL Press, 2000)

Kochav, Sarah: Israel: A Journey Through the Art and History of the Holy Land (Steimatzky, 2008)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Prag, Kay: Israel & the Palestinian Territories: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 2002)

Stiles, Wayne: “Sights and Insights: Where happy explorers go to dig”, Jerusalem Post, May 30, 2011

Vamosh, Miriam Feinberg: Beit She’an: Capital of the Decapolis (Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority, 1996)