West Bank

The greatest of the ancient monasteries dotting the wilderness of the Judaean Desert, Mar Saba hangs dramatically down the cliff edge of a deep ravine.

The grey-domed Greek Orthodox complex was established in the 5th century by St Sabas (Mar Saba in Arabic), a monk from central Turkey, and was largely rebuilt following a major earthquake in 1834.

Its remote location is 15 kilometres east of Bethlehem, off route 398 and reached down a steep road.

During its heyday the monastery was home to more than 300 monks. Though it remains a functioning desert monastery, its numbers have dropped to fewer than 20 in the 21st century.

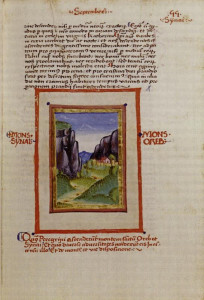

Occupied almost continuously since its founding, Mar Saba ranks with St Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula as one of the oldest inhabited monasteries in the world.

It also provides an enduring reminder of the age-old tradition of holy people leaving behind worldly distractions and seeking God in the solitude of the desert.

Part of the Mar Saba tradition is the exclusion of women visitors. They may only look over the complex from a vantage point called the Women’s Tower — built, according to tradition, by St Sabas’ mother, who was also forbidden to enter the monastery.

Saint’s body returned from Venice

A thick wall and slit-like windows give Mar Saba the appearance of a fortress. These defensive features recall plunder by the Persians in 615 and attacks from Bedouins in the following centuries.

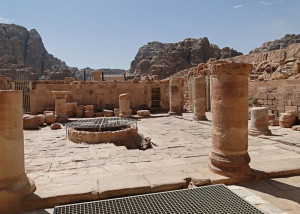

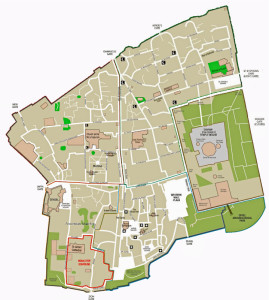

What began as a series of cell-caves along two kilometres of cliffs has been consolidated into a complex containing two churches, several chapels, a common dining room, kitchen storerooms, 14 cisterns, cells for monks and a hostel for visitors.

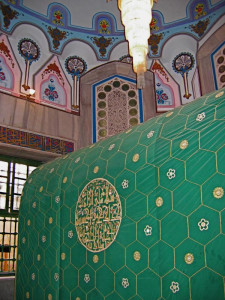

From the entrance, a low door in the western wall, a stepped passageway descends to the central courtyard. In the centre is a hexagon-shaped dome which was once the tomb of St Sabas.

During the Crusades the saint’s body was taken to Venice. Pope Paul VI arranged for its return after his Holy Land visit in 1964, and it now lies in a glass case in the main church.

This church, with a large blue dome and small bell tower, is dedicated to the Theotokos (Mother of God).

From the entrance area, a stairway leads to a series of small chapels — one in the cramped cave where a brilliant monk, St John Damascene, spent 20 years in the 8th century writing classic defences of Christianity against heresy and Islam.

On the northwest side of the courtyard is the second church, built into a grotto in the rock. It is dedicated to St Nicholas.

The skulls of monks killed by Persians invaders are displayed in the sacristy and their bones are collected behind a grille.

In contrast to the austere simplicity of the monks’ lifestyle, church and chapel walls glitter with the gold of innumerable icons, many donated to the monastery by the Russian government in the 19th century.

Holiness attracted other hermits

Mar Saba clings to one side of the Kidron Valley — the valley that begins between the Temple Mount and Mount of Olives in Jerusalem and runs eastward to the Dead Sea.

At the foot of the monastery, beneath three great buttresses that support the wall of the dining room, kitchen, storehouse and bakery, is a walled-in space containing the spring that attracted St Sabas to the site. The Kidron stream is dry in summer.

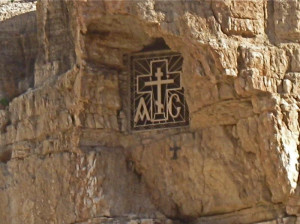

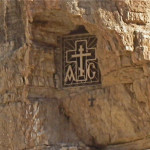

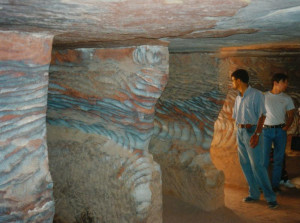

Across the valley is a cave where St Sabas spent five years in solitude. The opening is protected by a metal grille with a cross set between the letters A and C. Inside an entrance lower down, two ladders climb a 6-metre shaft to the simple cave, containing a rock-cut bench and a prayer niche cut into the eastern wall.

St Sabas had been a monk for 18 years before he sought seclusion in the Kidron Valley. Other hermits, attracted by his holiness, settled nearby and their cluster of cells led to the founding of Mar Saba.

A legacy from his mother and the arrival of two monks who had been architects paved the way for the construction of a large church and communal facilities.

St Sabas founded several other monasteries and became superior of all the hermit monks of Palestine. He is credited with taming a lion that tried to eat him, and vowing never to eat apples because he believed Eve tempted Adam with this fruit.

Monks developed Orthodox worship

Originally the monks of Mar Saba meditated in isolation in their caves from Monday to Saturday, then gathered to spend Saturday night in prayer together before celebrating Mass at dawn on Sunday.

They returned to their caves on Sunday evening, taking food for the following week and palm branches and rushes for their daily work of making rope, baskets and mats to be sold in Jerusalem to finance the monastery.

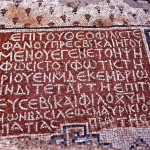

The monks of Mar Saba made a crucial contribution to the development of the liturgy in the Orthodox Church. They compiled a typicon — a book of directions for worship services and ceremonies — that became the standard for the Orthodox world up till the 19th century.

Administered by: Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem

Tel.: 972-2-2773135

Open: Open daily except Wednesdays and Fridays, 8am-4pm (ring bell). Only men may enter monastery; women are admitted only to Women’s Tower.

- Mar Saba from above (Steve Peterson)

- Main entrance to Mar Saba (Steve Peterson)

- Domes and buttresses of Mar Saba (Steve Peterson)

- Towers, buttresses and domes of Mar Saba (Matanya)

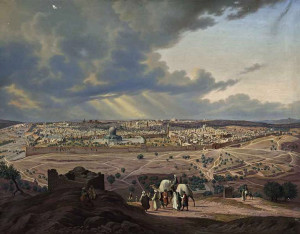

- Impression of Mar Saba in 1839, by David Roberts (Library of Congress)

- Shepherd leading sheep along Kidron stream near Mar Saba (© Clara Bonnet)

- Medieval icon of St Sabas (Wikimedia)

- Close-up of eastern buttresses and veranda (© Deror Avi)

- Steps down to the walled-in spring at Mar Saba (© Deror Avi)

- Former tomb of St Sabas (Sir Kiss)

- Monastery structure in Kidron Valley near Mar Saba (© Deror Avi)

- Mar Saba in its Kidron Valley setting (© Deror Avi)

- Remains of St Sabas in main church of Mar Saba (Adriatikus)

- Church domes at Mar Saba (© Deror Avi)

- Monks’ caves near Mar Saba (© Deror Avi)

- Cave of St Sabas (© Clara Bonnet)

- Kidron Valley near Mar Saba (© Deror Avi)

- Mar Saba from the north-east (© Deror Avi)

- Mar Saba and the Kidron stream (© Deror Avi)

- Skulls of martyred monks displayed at Mar Saba (Elad.lub)

- Defensive wall around Mar Saba (Kaasmail)

- Women’s Tower at Mar Saba (© Deror Avi)

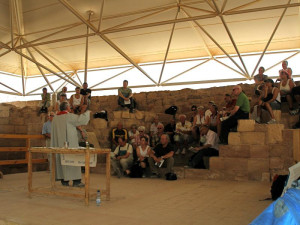

- Visiting priest in cave of St John Damascene (© Gregory Edwards)

- Women’s Tower standing apart from monastery at Mar Saba (© Deror Avi)

- Mar Saba from Kidron Valley (Kaasmail)

References

Bourbon, Fabio, and Lavagno, Enrico: The Holy Land Archaeological Guide to Israel, Sinai and Jordan (White Star, 2009)

Inman, Nick, and McDonald, Ferdie (eds): Jerusalem & the Holy Land (Eyewitness Travel Guide, Dorling Kindersley, 2007)

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Prag, Kay: Israel & the Palestinian Territories: Blue Guide (A. & C. Black, 2002)

Walker, Peter: In the Steps of Jesus (Zondervan, 2006)