New Zealand pilgrims see Jesus wherever they go in Galilee

by JOY COWLEY

NZ Catholic: July 15-28, 2007

Christians in Israel call the Holy Land “the Fifth Gospel”. They say that Jesus speaks through the landscape, thus opening up the other four Gospels. We found this true in ways we’d not expected. There we were, 47 NZ Catholic pilgrims, in the land of Jesus with Jesus. The four Gospels would never be the same for us.

Our arrival at Tel Aviv airport had been surprisingly easy. To encourage tourism, Israeli authorities have made security checks less intimidating. We walked out of customs, into the care of Harvest Pilgrimages’ avuncular agent Gabriel, guide Salah and driver Obadiah. By the time our bus wound down through the streets of Tiberias to the shore of Galilee, we were as excited as children on Christmas Eve.

Early morning by the Sea of Galilee is filled with peace. Some of us were up with the birds — trees shaking with twittering sparrows, swallows criss-crossing the sky, white herons flapping above the water. As the sun came up over the Golan Heights on the other side, and spread itself over the lake, we knew that our Lord saw such a morning as he cooked fish on a charcoal fire. Later, we would eat the same kind of fish — telapia, known in Galilee as St Peter’s fish.

That first day, on the way to Mt Tabor, our bus stopped briefly at Nain, where Jesus healed the widow’s son. A woman followed by a goose and two cats opened the church door for us, while several children appeared with hands held out like cups for shekels. We obliged. Why not? We were in celebratory mood.

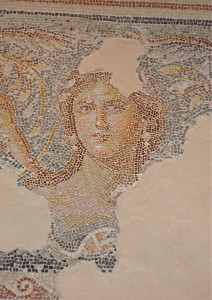

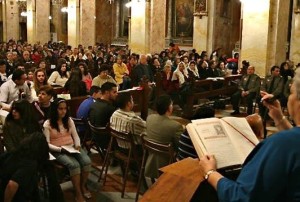

We climbed back in the bus and minutes later were on the top of Mt Tabor in the Franciscan Church of the Transfiguration, with its beautiful mosaics and sense of light. This was where Bishop Pat Dunn celebrated Mass with his cousin, Fr Tony Dunn, and, like many other churches we would visit, it has great acoustics. Our singing seemed to spiral up around the walls to echo in the mosaic-rich ceiling.

This was where Jesus allowed two of his disciples to see the radiance of his divine nature. We remembered friends in our prayers and felt privileged to be there.

That afternoon we went to Nazareth and the Church of the Annunciation, then the church at Cana where Jesus performed the first miracle. This is a popular place for the renewal of wedding vows. Because the church was full, we stood in the garden while Bishop Pat took couples through their vows. That night at dinner, no one volunteered to turn water into wine, but we found good chardonnay and merlot from the vineyards of Mt Carmel to complete the celebration.

On day two we stayed on and around the Sea of Galilee. In the morning we boarded a large wooden boat that looked as though it had sailed straight out of the Bible, borrowing an engine from the early 20th century on its way. We chugged towards a kibbutz on the other side but first stopped in the middle of the lake for prayer. Air and water were still, diamond bright with sun, and as Bishop Pat read from Scripture, we saw Jesus everywhere — asleep in the boat, calming a storm, walking on the water, with his disciples rowing to the other side.

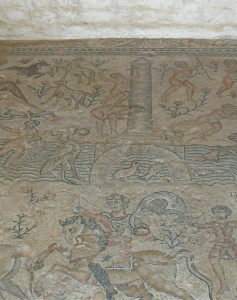

I reflected on “the other side”, the Decapolis which was pagan territory in Jesus’ time. Our Lord had seen his ministry as being only to the lost sheep of Israel. Yet in the pagan territory of the 10 towns he healed and taught, and people believed in the God of Israel.

What made Jesus change his mind? Scripture tells us it was the Syro-Phoenician woman who wanted healing for her daughter and wouldn’t take no for an answer. I gave thanks for that woman who made the good news of Jesus Christ available to the Gentiles.

The boat chugged to the jetty and we entered a kibbutz where we saw the 2000-year-old boat found in mud during a drought year. Back on the bus, we went to the excavated city of Capernaum and the church built over Peter’s house where Jesus stayed.

Some of us spent time in the ruins of the nearby fourth-century synagogue built on foundations of the synagogue where Jesus taught. In the hot, still air, the foundation stones seemed alive with his words.

The next stop was at the Church of the Primacy of Peter, on the shore of the lake, and here we had Mass in an outdoor chapel — a stone altar, stone seats in a circle under a large tree, the lake shimmering in the background. In this place, where Peter atoned for three denials with three statements of love, we too made our commitment: “Lord, you know that I love you.”

Because the West Bank road was open, we were able to drive around the western shore of the lake, through the Golan Heights, and back to the Church of the Beatitudes, before a visit to the baptismal site on the River Jordan.

The next day we made an unplanned return to the Church of the Beatitudes. We’d spent the morning at the crusader town of Akka (Acre) and the Carmelite church built over Elijah’s cave. Liturgy that afternoon was prepared for the Church of the Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes, but the venue was not available.

Our guide Salah took us back to the Church of the Beatitudes where we had Mass at an outdoor chapel on the hillside. The wind shook trees, flattened grass and clouded the lake with spray. We rejoiced in its energy. How often had Jesus walked on this hill in this wind?

We returned to the hotel, exhilarated and renewed, and were not surprised when Bishop Pat said he’d just looked up the ordinary readings for the day. What were they? The Beatitudes, of course.

Again, Jesus had been truly present in the Fifth Gospel — his turangawaewae [a Maori word meaning “a place to stand” or to feel connected].

Next issue: Jerusalem

Pilgrimage ends at Jerusalem but inner journey continues

by JOY COWLEY

NZ Catholic: July 29-August 11, 2007

Bags were loaded on the bus as 46 pilgrims, under the spiritual direction of Bishop Pat Dunn, prepared for the journey from the shores of Galilee to Jerusalem. We had been journeying with Jesus in his ministry. Now we were going to the region where he spent the first and last days of his Incarnation.

We had been travelling together for over a week and had become family to each other. Our days in Rome and Galilee were enriched with prayer and Eucharist, and warm with humour. Many of the lighter moments came from the Dunns — the bishop, his brother, Joe, and their cousin, Fr Tony, SM — who share genetic laughter.

Our co-ordinators Pat and Suzie McCarthy seemed to clone themselves in order to take care of each one of us. We didn’t know when they slept. And there was something else — a warmth cocooning the entire pilgrimage as though we were being held by something we did not want to name for fear of diminishing it with words.

The bus left the rich Jordan valley and travelled south through hard, dramatic desert to Jericho, where we looked at excavations of the city in Joshua’s time. The sun was turned up to fan bake and, apart from the green garden patch around Elisha’s spring, Jericho, ancient and modern, was cooked to the colour of dust.

Back in the air-conditioned bus, we moved on to Bethany, about two miles outside Jerusalem. Again, the past became present to us and we were in the company of Mary, Martha and Lazarus, good friends of Jesus.

Archaeologist and scholar Yigael Yadin has evidence that Bethany was once a village for Essene lepers and other outcasts. This could be so, for it was in Bethany that Jesus had a meal with Simon the leper. There is also a tradition that Lazarus had some disability. But we were not in Bethany to fill gaps in history. We were with the timeless Jesus, who was returning with his disciples from the Batanea area to the tomb where he would raise Lazarus from the dead.

We stopped in a narrow street and negotiated hazardous steps down to Lazarus’ tomb. The original entrance to the tomb is now closed up, part of the wall of a mosque, although the tomb itself is believed to be original.

Some of the holy sites visited are approximate, others actual. How do we know, for example, that Ein Karem is the birthplace of John the Baptist and the site of the Visitation? Our guide Salah explained. In an attempt to erase Christianity, the Romans built temples to Roman gods over the places venerated by the followers of Jesus. The temples served as markers for the Byzantine reclamation of holy sites.

We celebrated Jesus’ birth for most of our second day in the Jerusalem area, which meant going through the wall to Bethlehem and the Church of the Nativity. The high barrier cutting off the West Bank was covered with slogans, pro-Israeli government on one side and anti-Israeli government on the other, reminding us that this little country has never known prolonged peace.

But there is peace in abundance at the holy places. At Shepherds Field, we had Mass outside under the trees, and the angel song at Jesus’ birth seemed very real to us.

Conflict in Gaza gave us time to reflect on the tension of opposites: The child in the manger and Herod; Jesus and the Pharisees; a holy city and car bombings; angel song and gunfire.

Evil is a certainty but, somehow, it is tied to goodness. My perception is too limited for understanding, yet if I imagine a state of perfect peace, I see stagnancy. There is no growth without tension. It is a condition of human pilgrimage.

We were aware of this the next day when we journeyed with Jesus to Calvary. The morning’s walk through the old city began brightly enough, with crowds moving through security checkpoints to the Pool of Bethesda and the Wailing Wall where Jews from all nations were praying.

A group of Moroccans celebrated a Bar Mitzvah with drums and shofar, clapping and song. Married Hassid women with shaven heads covered by turbans rocked with their prayer books. Every crack in the wall was filled with bits of folded paper — notes to God about broken relationships, financial problems, babies, health, and maybe a word or two of praise.

We moved on through the old city and our pilgrim sky darkened. We had previously visited the House of Caiaphas and St Peter in Gallicantu, where Peter denied his Lord. Now we were doing the actual death walk with Jesus, the Via Dolorosa and the Stations of the Cross. Again we met the tension of opposites.

On both sides of this ancient road where our Lord carried his cross to Calvary were merchants trying to sell us stuffed toy camels and souvenir Jerusalem bags. Did traders also follow the crowd that condemned Jesus?

Mass at the Church of Calvary brought us to the heart of our faith. “Lord by your cross and Resurrection you have set us free.” We rested in sombre mood in the silence between the cross and the Resurrection. Here was the supreme example of the mystery of good and evil, horrifying darkness evolving into eternal light.

That night, Bishop Pat arranged for us a Holy Hour in the Garden of Gethsemane, where we wound back time again to keep watch with Jesus. For many of us, this hour of silent prayer with readings and Taize chant was a peak Jerusalem experience.

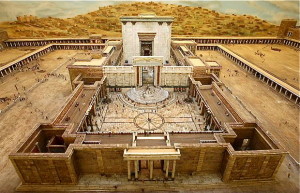

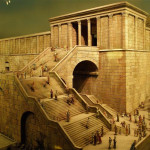

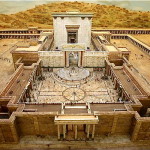

Our pilgrimage was almost over. We had time at the museum Shrine of the Book where we saw the Dead Sea Scrolls and a model of Jerusalem in the second temple era, plus a visit to Masada and the Dead Sea; but the journey with Jesus seemed to come to completion with a visit to Emmaus.

At Eucharist we were the disciples who walked with the risen Jesus to this place and our hearts burned within us. But had not our hearts been warm with his presence every day?

The last night was tinged with sadness — farewells, hugs, some tears. Still, it was only the outer journey of this pilgrimage that had ended. The inner journey would go on and on.