Israel

Jesus criticised the Galilean fishing village of Bethsaida for its inhabitants’ lack of faith. In contrast, at least three of its native sons — Peter, Andrew and Philip — responded to his call and gave up everything to follow him.

Jesus had performed several “deeds of power” in the area before his condemnation: “Woe to you, Bethsaida!” (Luke 10:13-14):

He gave sight to a blind man and, not far away, he taught and fed a crowd of 5000. And from the Bethsaida shore he was seen walking on the Sea of Galilee.

Despite the locals’ spiritual blindness, Bethsaida is one of the most frequently mentioned towns in the New Testament.

“Indeed Bethsaida, Chorazin and Tabgha — with Capernaum as the base’s midpoint — constituted the ‘evangelical triangle’, on the northwestern end of the Sea of Galilee, within which approximately 80% of Jesus’ public ministry was exercised, according to the synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke!” writes biblical scholar Daniel W. Casey.

A fishing village far from the water?

The first-century Roman writer Pliny the Elder called Bethsaida “one of four lovely cities on the Sea of Galilee”. Yet, like Capernaum and Chorazim, Bethsaida was abandoned and forgotten for many centuries.

In fact scholars are uncertain over whether there might have been two towns called Bethsaida, one on the west of where the River Jordan enters the Sea of Galilee, and the other on the east.

One site claimed by archaeologists to be Bethsaida is at et-Tell on the east of the Jordan, 2 kilometres north of the Sea of Galilee. Others favour the site of el-Araj, near the north-eastern shore of the lake.

The location of et-Tell — first suggested by the American scholar Edward Robinson in 1839 — presents a further puzzle: How could a fishing village be so far from the water? The reason offered is that the landscape has changed since the time of Jesus.

The suggestion is that an earthquake has lifted et-Tell and the Sea of Galilee has shrunk in size. In Christ’s day, according to biblical archaeologist Bargil Pixner, the Jordan River did not sweep in a large loop as it does today, but flowed straight into a shallow lagoon before reaching the lake, so a small part of Bethsaida lay on the west bank of the river.

At el-Araj, archaeologists in 2017 discovered a Roman-era (first- to third-century AD) bathhouse, which they suggested was evidence for a significant urban settlement at the site.

In 2019 they reported finding the remains of a large Byzantine-era church which they believed to be the Church of the Apostles, built over the house of the apostles Peter and Andrew. This church was described by a visiting bishop in 725.

Three years later the discovery of a mosaic inscribed with a petition to the “head and leader of the heavenly apostles” (assumed to be St Peter) strengthened el-Araj’s claim to be Bethsaida.

City destroyed and never rebuilt

In AD 30 — about the time Jesus was crucified — the local ruler, Herod the Great’s son Philip, raised the fishing village of Bethsaida to the status of a city and named it Bethsaida Julias (in honour of the wife of the Emperor Augustus).

Bethsaida Julias contained both Gentile (Syrian) and Jewish populations, and it apparently continued to exist after the Jewish Revolt in AD 66-74, but declined in the 3rd century and was probably destroyed by the Assyrian invasion in the 8th century.

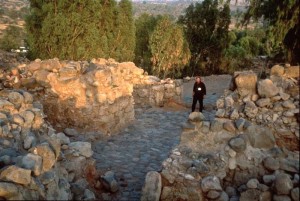

The excavation site of et-Tell is located in a public recreation area known as Jordan Park, close to the Yahudia Junction at the intersection of Routes 87 and 92.

Excavators say they have found a much older Iron Age site beneath a Hellenistic-Roman village. They believe this city was the ancient capital of the kingdom of Geshur, fortified with a massive city wall and a monumental gateway.

Their identifications include a house belonging to a fisherman and an apparent wine cellar. They also found a gold Roman coin from the 2nd century AD.

The excavators believe that the fishing village on the site was also an important centre of fish processing — drying and salting — in the time of Jesus and his disciples.

In Scripture:

Jesus curses Bethsaida: Luke 10:13-14, Matthew 11:20-22

Jesus cures a blind man: Mark 8:22-26

Administered by: Bethsaida Excavations Project (et-Tell)

- Ancient city gate at et-Tell/Bethsaida (© Israel Ministry of Tourism)

- Stele marking the winemaker’s house at et-Tell/Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

- Drawing of the fisherman’s house from the Hellenistic-Roman period at et-Tell/Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

- Carved stone decoration from a building in et-Tell/Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

- Et-Tell/Bethsaida with the Sea of Galilee in the distance (Seetheholyland.net)

- Path among the ruins of et-Tell/Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

- Et-Tell/Bethsaida stele in memory of Jesus’ calling of his fishermen disciples (Seetheholyland.net)

- Drawing of the winemaker’s house from the Hellenistic-Roman period at et-Tell/Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

- Ruins in et-Tell/Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

- Artist’s impression of biblical Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

- Plain of Bethsaida from the north-west (© BiblePlaces.com)

- Stele marking a street in et-Tell/Bethsaida (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Bechtel, F.: “Bethsaida”, The Catholic Encyclopedia (Robert Appleton Company, 1914)

Charlesworth, James H.: The Millennium Guide for Pilgrims to the Holy Land (BIBAL Press, 2000)

Daniel W. Casey, Jr, “House of the Fishers”, Holy Land, autumn 1997

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (Oxford University Press, 2005)

Pixner, Bargil: With Jesus Through Galilee According to the Fifth Gospel (Corazin Publishing, 1992)

Rainey, Anson F., and Notley, R. Steven: The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Carta, 2006)

Shpigel, Noa, and Schuster, Ruth: “The Lost Home of Jesus’ Apostles Has Just Been Found, Archaeologists Say”, Haaretz, August 8, 2017

Schuster, Ruth: “Archaeologists Claim to Have Found the Church of the Apostles by Sea of Galilee”, Haaretz, July 18, 2019

Schuster, Ruth: “Archaeologists Find Entreaty to St. Peter in Early Church by Sea of Galilee”, Haaretz, August 10, 2022

External links

Bethsaida (BiblePlaces)

Bethsaida (BibleWalks)

Bethsaida (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Bethsaida Excavations Project (University of Nebraska, Omaha)

Biblical Sites: Is et-Tell Bethsaida? (Bible Archaeology Report)

Biblical Sites: Is el-Araj Bethsaida? (Bible Archaeology Report)