Jordan

The baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist, the act that launched Jesus’ public ministry, most likely took place on the Jordanian side of the Jordan River, in a perennial riverbed called the Wadi Al-Kharrar.

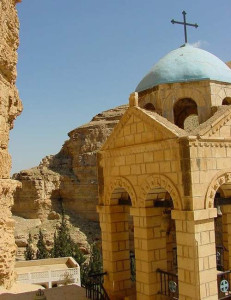

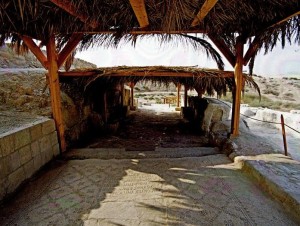

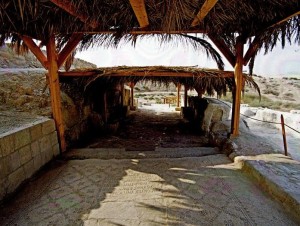

Shelter over remains of a church at the Baptism Site (Alicia Bramlett)

Here the remains of more than 20 Christian sites have been discovered, including several churches, a prayer hall, baptismal pools and a sophisticated water reticulation system. These date back to the Roman and Byzantine periods.

Excavations at Bethany Beyond the Jordan began only in 1996. Before then the area had been a minefield on the front line between Jordan and Israel, whose border is the Jordan River.

The 1994 peace treaty between Jordan and Israel prepared the way for access by archaeologists and church officials. Jordanian authorities have built a new road, a visitors’ centre and walkways. Several Christian denominations have built churches, the most prominent being the gold-domed Greek Orthodox Church of St John the Baptist.

The baptismal site of Bethany Beyond the Jordan (John 1:28) is near the southern end of the Jordan River, across from Jericho and 8 kilometres south of the King Hussein (or Allenby) Bridge. It is 40 minutes by car from the Jordanian capital of Amman.

It should not be confused with the Bethany on the eastern slope of the Mount of Olives, near Jerusalem, where Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead.

Stream flows from oasis

At the head of the Wadi Kharrar, springs emerge from the barren landscape to create a small oasis of tamarisk and palm trees, reeds, grasses and shrubbery. From here the Wadi Kharrar stream flows eastward to the Jordan River, its 2-kilometre route flanked by thick vegetation and identified by the murmur of running water.

Lush vegetation beside the Jordan River (© Visitjordan.com)

The fresh water of the Wadi Kharrar stream would have been more suitable for baptisms than the murkier Jordan River, which in John the Baptist’s time was also subject to heavy seasonal flooding.

The area adjacent to the baptismal site of Bethany Beyond the Jordan (called Al-Maghtas in Arabic) has many other biblical associations.

Near here, it is believed, Joshua led the Israelites across the Jordan River to the Promised Land after the waters miraculously stopped flowing (Joshua 3:14-16).

Elijah — a prophet who is often associated with John the Baptist — also crossed the Jordan River on dry ground in this area, and was then taken up to heaven in a chariot of fire (2 Kings 2:8-11).

In the New Testament, Jesus withdrew to Bethany Beyond the Jordan after being threatened with stoning in Jerusalem (John 10:31-40).

Early Christian pilgrims visited Bethany Beyond the Jordan on a route that went from Jerusalem to Jericho, across the Jordan River and then to Mount Nebo.

Precise spot is unknown

Pilgrims renew baptismal promises around a font of water from the Jordan River (Seetheholyland.net)

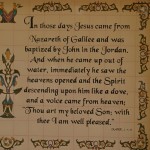

John the Baptist “went into all the region around the Jordan, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (Luke 3:3). The Jordan River has changed course over the centuries and the precise spot where John baptised Jesus will probably never be positively identified.

All four Gospel writers mention Jesus’ baptism, but only John specifies the location as Bethany Beyond the Jordan. Documentary evidence favours identifying this location as Wadi Al-Kharrar or Al-Maghtas.

Not all scholars accept this identification. Some prefer a location north of the Sea of Galilee, by the Yarmouk River, where Elijah, hiding from the wrath of King Ahab, is believed to have been fed by a raven (1 Kings 17:2-6).

Identification was made more difficult by the Christian scholar Origen, who lived in Palestine in the 3rd century. Unaware of any Bethany on the east side of the Jordan River, he suggested the placename in John’s Gospel should be Bethabara (which was on the west of the river). Some New Testament translators followed his suggestion. It even appears in the King James Version of the Bible.

Jesus’ baptism is also commemorated on the western bank of the Jordan River, at a site in Israel called Qasr Al-Yahud (see below).

Church was built on arches

Pilgrims as far back as 333 described visits to the baptism site of Bethany Beyond the Jordan. An account in 530 said it was marked by a marble pillar on which an iron cross had been fastened.

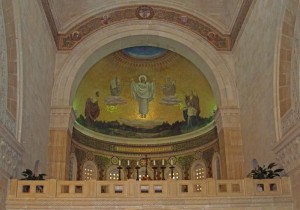

The 6th-century pilgrim Theodosius described a church built there by the Byzantine emperor Anastasius I. He said this square-shaped church was built on high arches to allow flood waters to pass underneath. Archaeologists believe they have uncovered remains of the piers on which the church was built.

Later pilgrims referred to a small church said to have been built “on the place where the Lord’s clothes were placed”.

The Wadi Al-Kharrar was also the centre of an active monastic life. Hermits lived in caves carved into the soft limestone, gathering weekly for a common liturgy.

A monastery with four churches developed between the 4th and 6th centuries on Tell Mar Elias (St Elijah Hill), just above the springs that feed the stream. A hostel between the monastery and the river provided lodging for pilgrims, who would immerse themselves in the waters.

The baptismal site was particularly revered by Russian pilgrims prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917. They would arrive carrying their shrouds which they would wear as they baptised each other in the river.

One church was built around a cave

In an area of several square kilometres, now called the Baptism Archaeological Park, the Jordanian Department of Antiquities has surveyed, excavated and conserved a series of ancient remains.

Mosaics from a church floor (© Visitjordan.com)

These include a walled monastery containing at least four churches and chapels, a prayer hall, a sophisticated water reticulation and storage system and three plastered pools. The wall was intended to prevent erosion, rather than protect against attack.

The discoveries include remains of foundations and walls, mosaic floors, fine coloured stone pavements, Corinthian capitals, column drums and bases, and hermits’ cells and caves.

One of the churches appears to have been built around a natural cave containing fresh spring water — possibly the cave that Byzantine pilgrims called “the cave of John the Baptist”.

The development of facilities for pilgrims has been encouraged by the Jordanian royal family. These facilities include a new road from the Dead Sea area, a visitors’ centre, and paths and walkways to the most important religious and archaeological sites.

In 2015 Bethany Beyond the Jordan was designated a World Heritage site.

Commemoration moved to western bank

Greek Orthodox Church of St John the Baptist at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Seetheholyland.net)

The religious sites in the Wadi Al-Kharrar area were gradually abandoned from the time of the Muslim conquest, in the middle of the 7th century. Pilgrims from Jerusalem no longer ventured across the Jordan River, so they commemorated the baptism of Jesus near Qasr Al-Yehud on the western bank.

This site is marked by the large medieval-era Greek Orthodox Monastery of St John the Baptist, built on Byzantine ruins and clearly visible from across the river.

Access to the area around Qasr Al-Yehud has also been difficult in modern times. From 1967 until 1994 it was also in a military zone and heavily mined. It was open only twice a year for pilgrims celebrating their feasts of the baptism of Christ, in January for the Orthodox and October for the Catholics. In 2011 it was opened to the public.

By the end of 2018, access to three of the seven monasteries in the area — Greek Orthodox, Ethiopian and Franciscan (Catholic) — had been cleared of mines.

While Qasr Al-Yehud was inaccessible, the long-established Kibbutz Kinneret began running a substitute site at Yardenit, near the southern end of the Sea of Galilee, with modern facilities and shady eucalyptus trees. It has been receiving more than half a million visitors a year, many receiving baptism or renewing their baptismal promises in the Jordan River.

In Scripture:

Elijah is taken up to heaven: 2 Kings 2:1-14

The preaching of John the Baptist: Luke 3:2-14

John baptises Jesus: Matthew 3:13-17; Mark 1:9-11; Luke 3:21-22; John 1:29-34

The witness of John the Baptist: John 1:19-28

Jesus retreats beyond the Jordan for safety: John 10:40

Administered by:

Department of Antiquities of Jordan; Jordan Valley Authority; Greek Orthodox Church

Tel.: 962-5-3590360

Open: Winter 8am-4pm (last entry 3pm); summer 8am-6pm (last entry 5pm)

-

-

Remains of Christian sites at Bethany Beyond the Jordan, with steps leading to Church of John the Baptist, under far shelter (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

New Catholic church under construction at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Piers for arches on which one of the churches at Bethany Beyond the Jordan was built (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

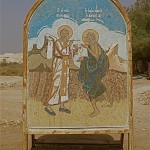

St Mary of Egypt receiving Communion from St Zosimas, as depicted at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Icon in Church of St John the Baptist at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Pilgrims renew baptismal promises around a font of water from the Jordan River (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Bones of a 6th-century monk in the Church of John the Baptist (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Access to the Jordan River from Jordanian (left) and Israeli sides (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

One of the new churches at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Approach to the Jordan River from the Jordanian side (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Greek Orthodox Church of St John the Baptist at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Inside the “Cave of John the Baptist” (© Baptismsite.com)

-

-

Hermit cells overlooking the Jordan River (© Baptismsite.com)

-

-

Remains of the mosaic floor of the upper basilica (© Baptismsite.com)

-

-

Shelters over the remains of churches built in memory of the Baptism of Christ (© Baptismsite.com)

-

-

Excavations at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (© Visitjordan.com)

-

-

Mural of Elijah’s fiery ascent into heaven, in the Orthodox church (David Bjorgen)

-

-

Mosaic pattern at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (© Visitjordan.com)

-

-

Dome of Orthodox church at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Bob McCaffrey)

-

-

Mosaics from a church floor (© Visitjordan.com)

-

-

Mural of Jesus approaching John the Baptist, in the Orthodox church (David Bjorgen)

-

-

Close-up of the Church of John Paul lI (© Visitjordan.com)

-

-

Mural of Jesus’ Baptism, in the Orthodox church (David Bjorgen)

-

-

Excavations at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (© Visitpalestine.ps)

-

-

Excavation of a pool at the Baptism Site in Jordan (© Visitjordan.com)

-

-

Lush vegetation beside the Jordan River (© Visitjordan.com)

-

-

Orthodox Church of St John the Baptist at the Baptism Site (David Bjorgen)

-

-

Arch of the Church of John Paul II, the pope who celebrated Mass here in 2000 (© Baptismsite.com)

-

-

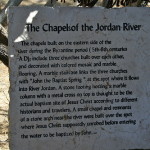

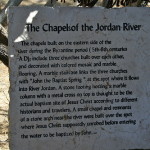

Sign at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Bob McCaffrey)

-

-

Shelter over remains of a church at the Baptism Site (Alicia Bramlett)

-

-

Four piers show where Byzantine church is believed to have been built (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Russian Orthodox church at Bethany Beyond the Jordan, with mosaic depicting President Vladimir Putin at its opening in 2012 (Seetheholyland.net)

-

-

Evangelical Lutheran Church at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Ben Gray / ELCJHL)

-

-

Sign quoting King of Jordan at Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Seetheholyland.net)

References

Beitzel, Barry J.: Biblica, The Bible Atlas: A Social and Historical Journey Through the Lands of the Bible (Global Book Publishing, 2007)

Fletcher, Elaine Ruth: “Searching for the site of Jesus’ Baptism”, Religion News Service, January 1, 2000

Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P.: The Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Israel, Jordan and the Sinai (Continuum Publishing, 1996)

Gonen, Rivka: Biblical Holy Places: An illustrated guide (Collier Macmillan, 1987)

Khouri, Rami: “Where John Baptized: Bethany Beyond the Jordan”, in Exploring Jordan: The Other Biblical Land (Biblical Archaeological Society, 2008)

Laney, J. Carl: “The Identification of Bethany Beyond the Jordan”, from Selective Geographical Problems in the Life of Christ, doctoral dissertation (Dallas Theological Seminary, 1977)

Lazaroff, Tovah: “Israel clears landmines from seven monasteries by Jesus’ Baptismal site”, Jerusalem Post, December 9, 2018

Miller, Charles: “Bethany Beyond the Jordan” (CNEWA World, January 2002)

Pixner, Bargil: With Jesus Through Galilee According to the Fifth Gospel (Corazin Publishing, 1992)

Rainey, Anson F., and Notley, R. Steven: The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Carta, 2006)

Walker, Peter: In the Steps of Jesus (Zondervan, 2006)

Wooding, Dan: “Thousands visit Bethany Beyond the Jordan”, Assist News Service, January 15, 2007

External links